We consider the inverse problem of reconstructing the spatial layout of a place, a home floorplan for example, from a user’s movements inside that layout. Direct inversion is ill-posed since many floorplans can explain the same movement trajectories. We adopt a diffusion-based posterior sampler to generate layouts consistent with the measurements. While active research is in progress on generative inverse solvers, we find that the forward operator in our problem poses new challenges. The path planning process inside a floorplan is a non-invertible, non-differentiable function, and causes instability while optimizing using the likelihood score. We break-away from existing approaches and reformulate the likelihood score in a smoother embedding space. The embedding space is trained with a contrastive loss which brings compatible floorplans and trajectories close to each other, while pushing mismatched pairs far apart. We show that a surrogate form of the likelihood score in this embedding space is a valid approximation of the true likelihood score, making it possible to steer the denoising process towards the posterior. Across extensive experiments, our model CoGuide produces more consistent floorplans from trajectories, and is more robust than differentiable-planner baselines and guided-diffusion methods.

Abstract

Introduction

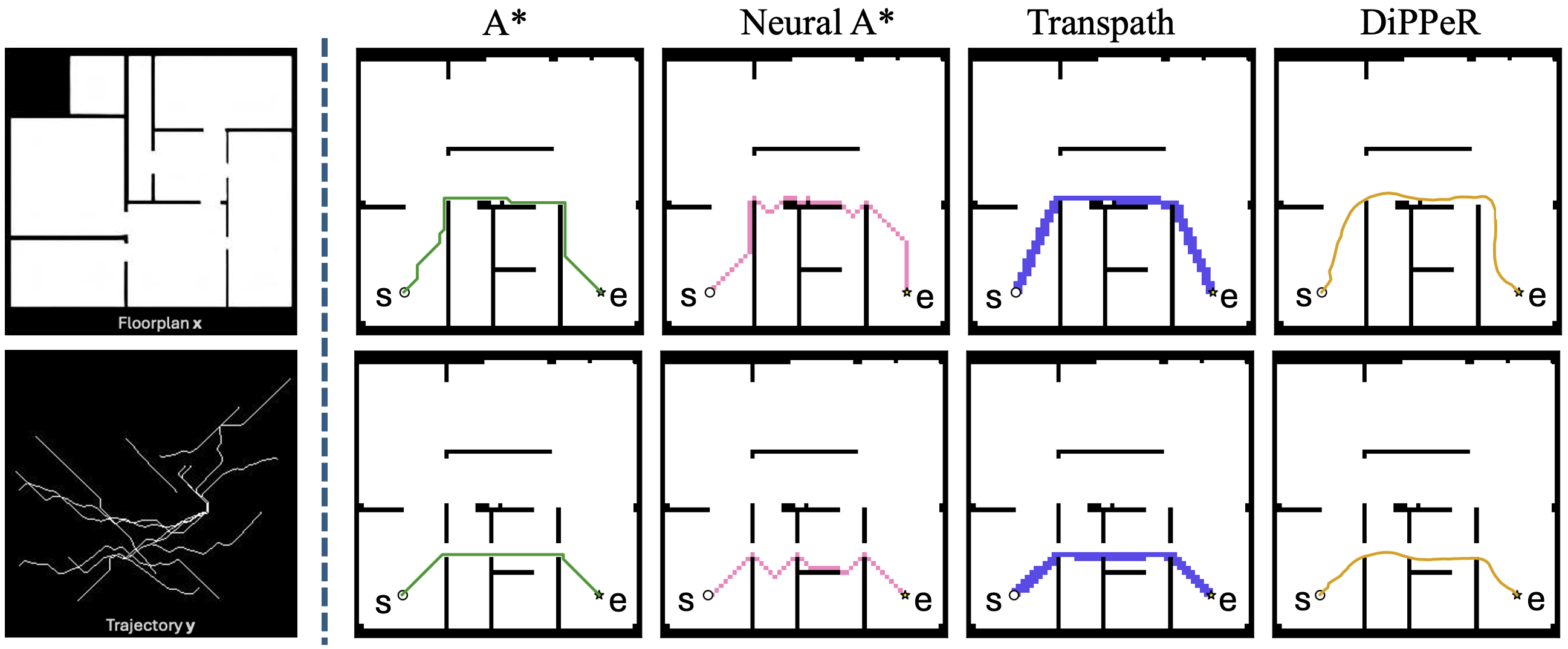

In our setting, the measurement arises from a forward process that reflects human path planning. Because the path-planning operator is non-linear, non-differentiable, and only partially observed, small changes in layout can cause drastic changes in the planned path. The figure below illustrates this: the left panel shows a floorplan with the measured trajectory, while the right panel shows how planners such as A*, Neural A*, TransPath, and DiPPeR can select very different paths to a slight layout change (bottom row) triggering large path differences.

Method

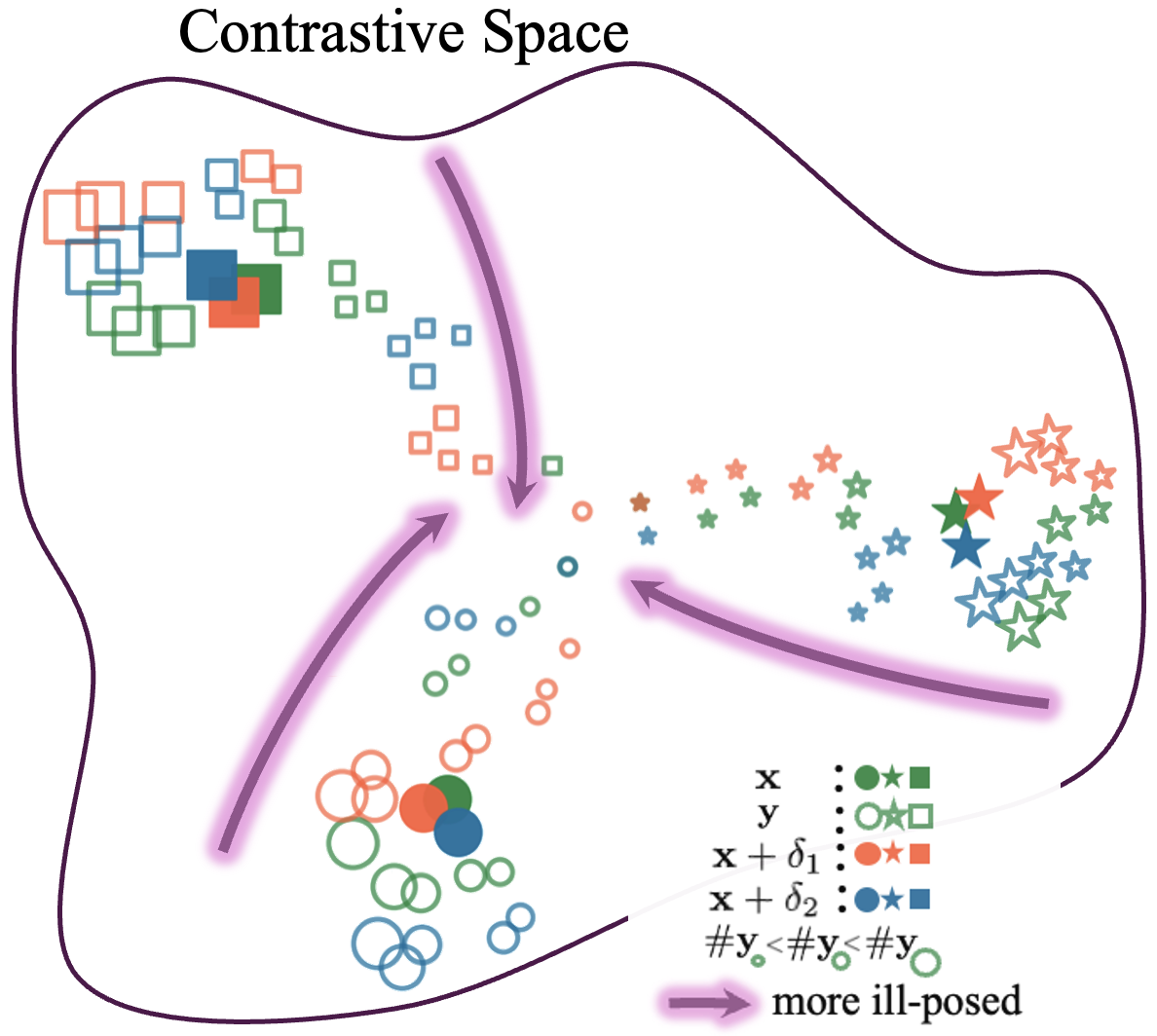

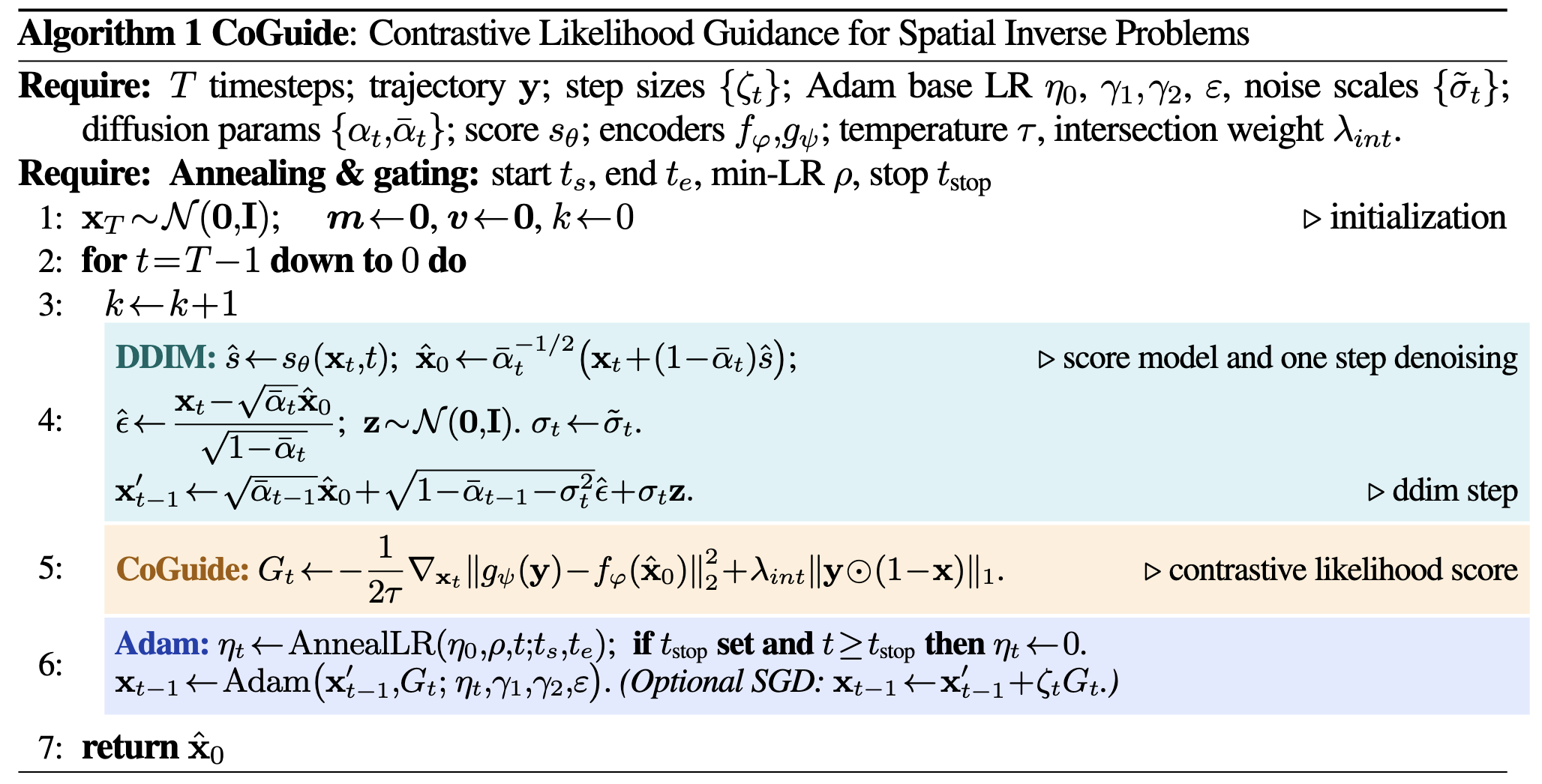

We address the concerns raised by the forward operator by guiding a diffusion prior with a surrogate likelihood from a smooth, contrastive trajectory–layout space instead of the direct pixel-space likelihood. The resulting contrastive space (shown right) clusters compatible trajectory–layout pairs while pushing apart incompatible pairs. This yields a smoother likelihood score that is more amenable to gradient-based optimization. The contrastive model is trained with a combination of Supervised Contrastive Loss (SupCon), and an alignment loss. We also adapt Adam and DDIM into the reverse-time update to improve convergence and speed. The complete CoGuide algorithm is shown below.

Algorithm

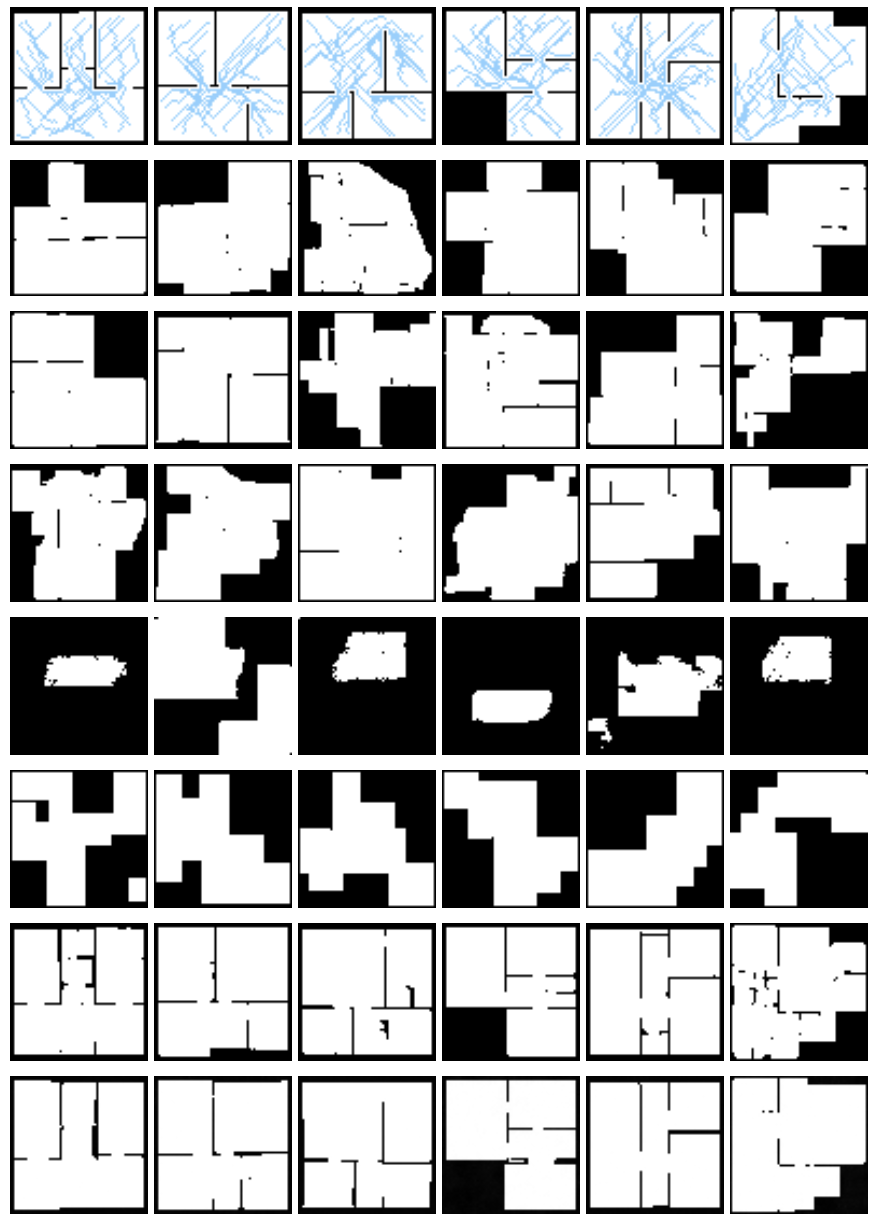

Reverse Denoising Process

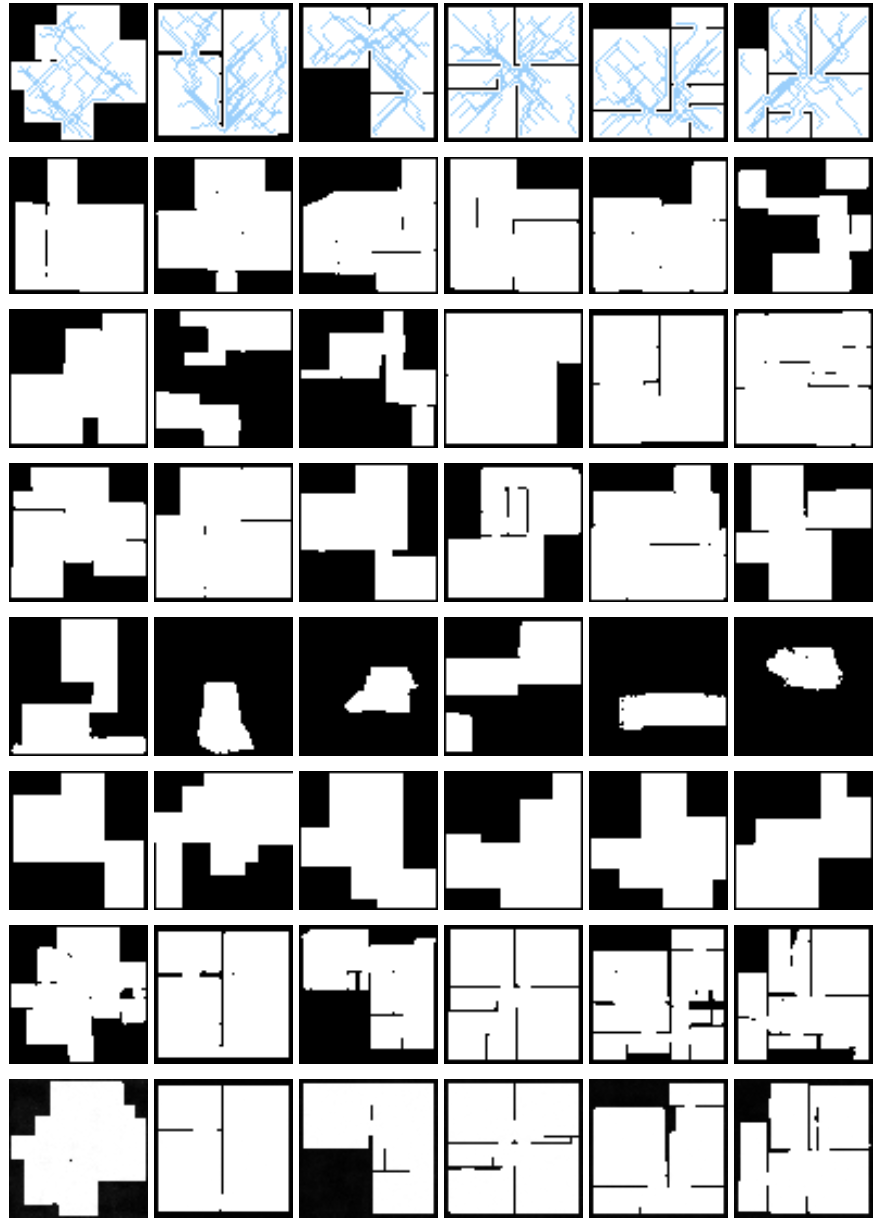

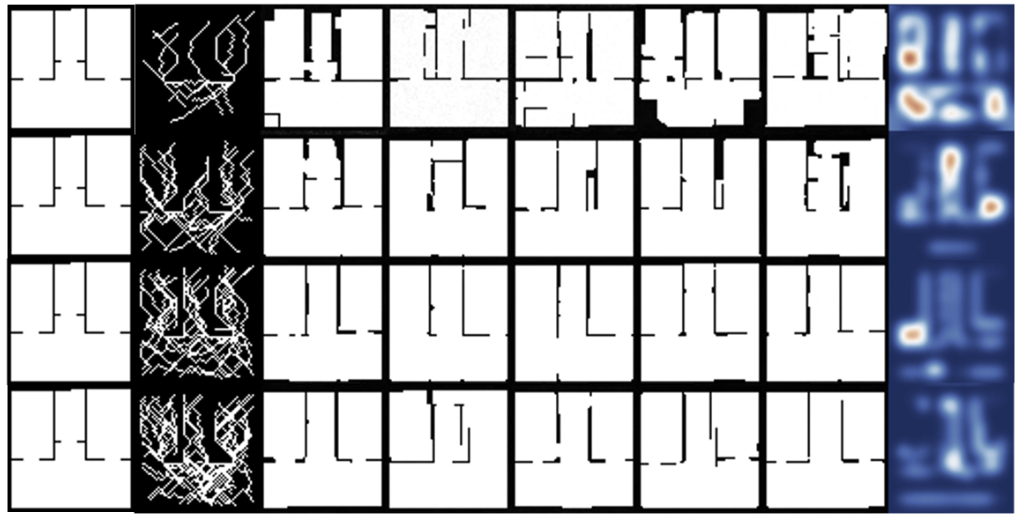

Below, we show several examples of the reverse denoising process under CoGuide that samples from the posterior \(p(\mathbf{x}|\mathbf{y})\). Each image has 3 columns: the leftmost column is the ground truth floorplan \(\mathbf{x}\), the middle column is the measured trajectory \(\mathbf{y}\), and the rightmost column shows the denoising process \(\mathbf{x}_T \rightarrow \mathbf{x}_0\) , from pure noise to the final output.

Results

Qualitative

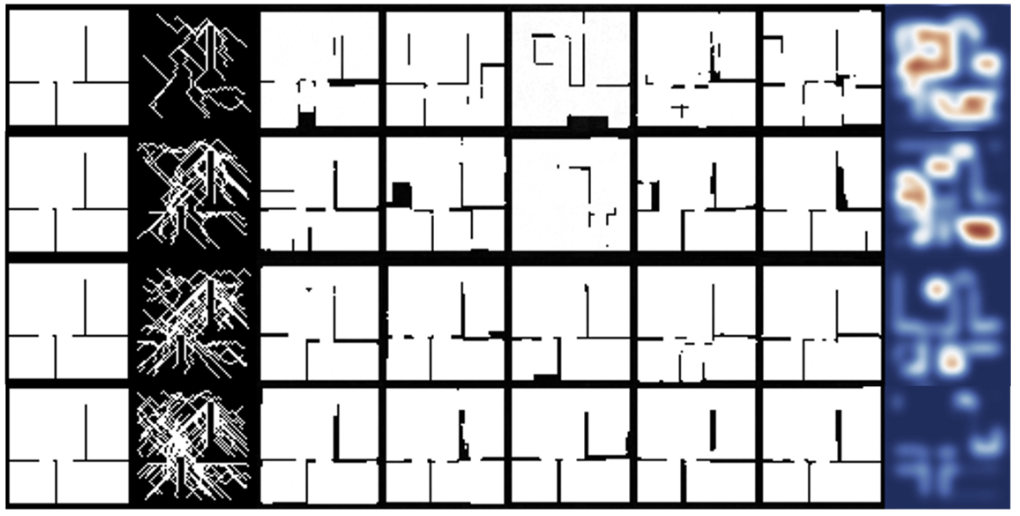

CoGuide produces floorplans that align with the measured trajectory while avoiding common artifacts from planner-guided methods (see below). DPS+planner variants, DiffPIR, and DMPlug frequently violate trajectory consistency or introduce spurious walls. Although CFG can score well on metrics, its visuals are not always faithful and generates artifacts. CoGuide yields cleaner, trajectory-consistent layouts across diverse test scenes.

Quantitative

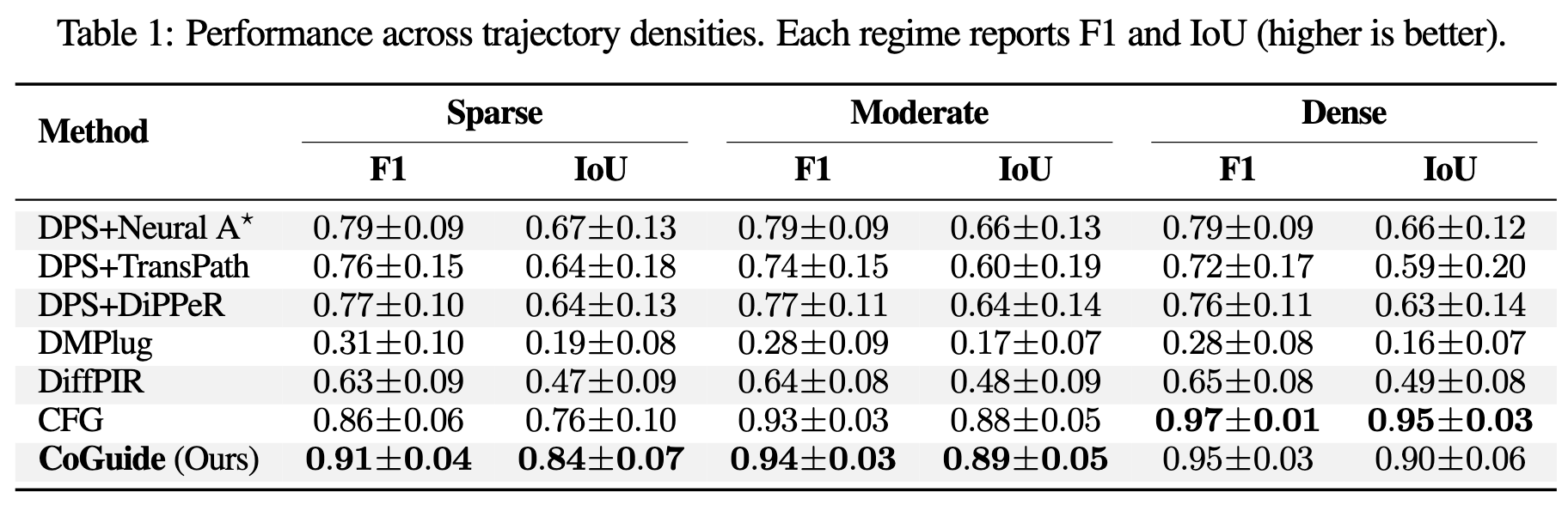

In the table shown below, we report F1/IoU (mean ± std) across three trajectory-density regimes (low, medium, high). CoGuide leads in the sparse and moderate settings, surpassing CFG and DPS variants, and remains competitive in the dense regime where CFG is strongest. Overall, CoGuide consistently outperforms DPS-based (differentiable) planners, DiffPIR, and DMPlug.

Ablations

Noise Robustness

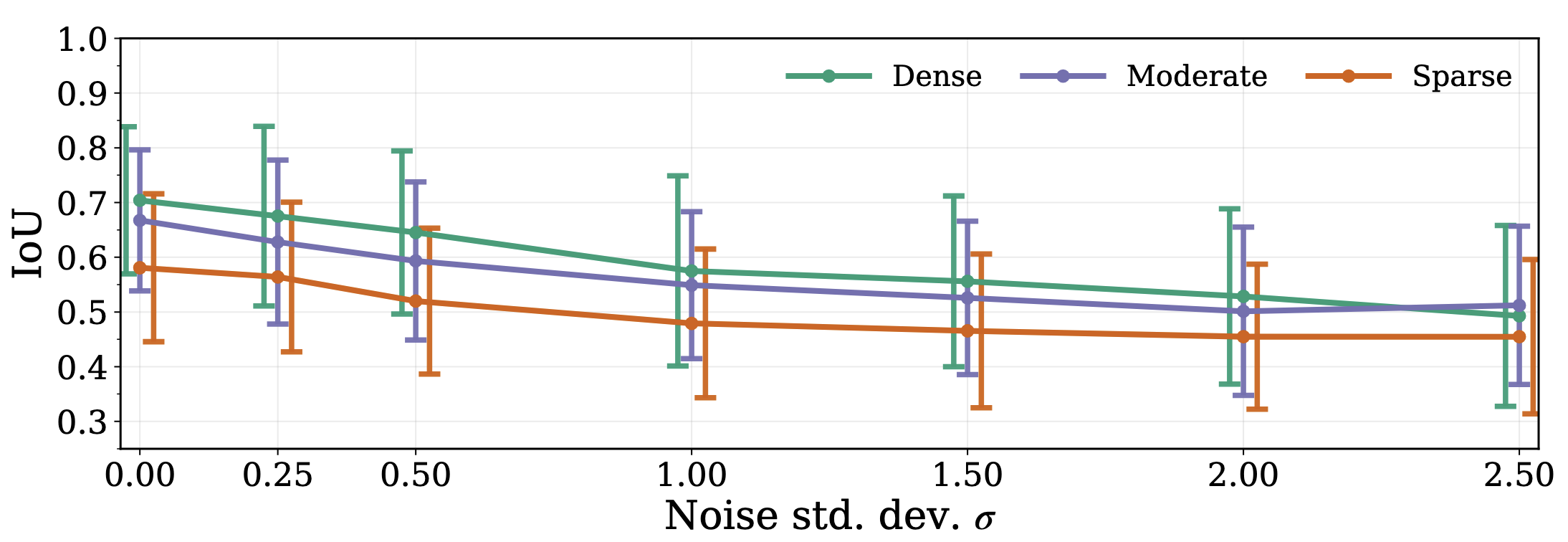

To model real-world localization errors, we inject Gaussian noise during trajectory generation and sweep the noise standard deviation across densities. The resulting comparison plot is shown below. As noise increases, performance degrades gracefully; higher trajectory density mitigates the impact and sustains stronger accuracy.

Optimizers and Samplers

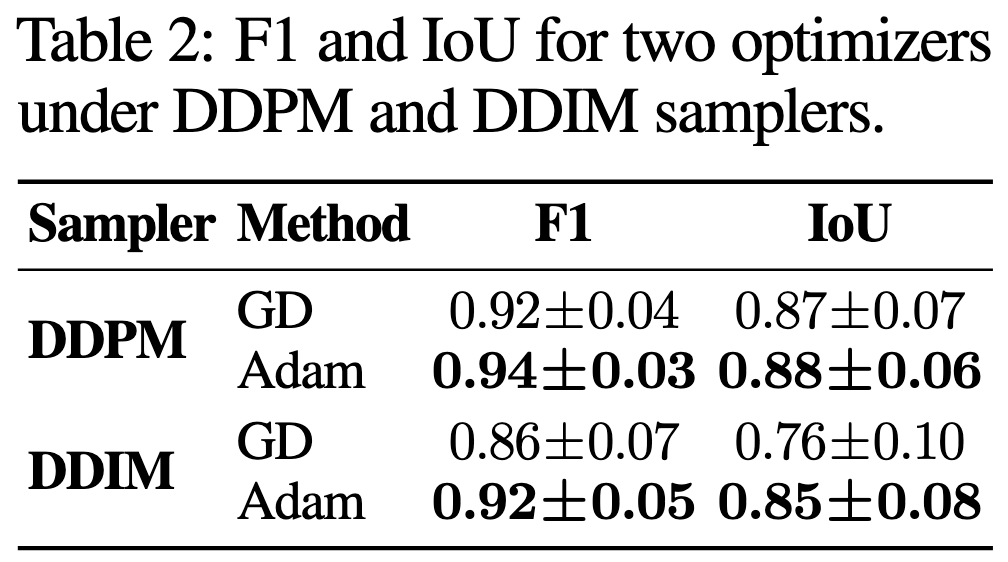

We incorporate Adam into the reverse-time diffusion and compare against standard gradient descent under both DDPM and DDIM samplers. The table below demonstrates that Adam consistently improves convergence and final metrics across samplers, while DDIM achieves comparable accuracy to DDPM with fewer steps.

- DDPM vs. DDIM: speed–accuracy trade-off is minimal under our guidance.

- Adam vs. SGD: Adam converges faster; final metrics are comparable.

Uncertainty vs. Trajectory Density

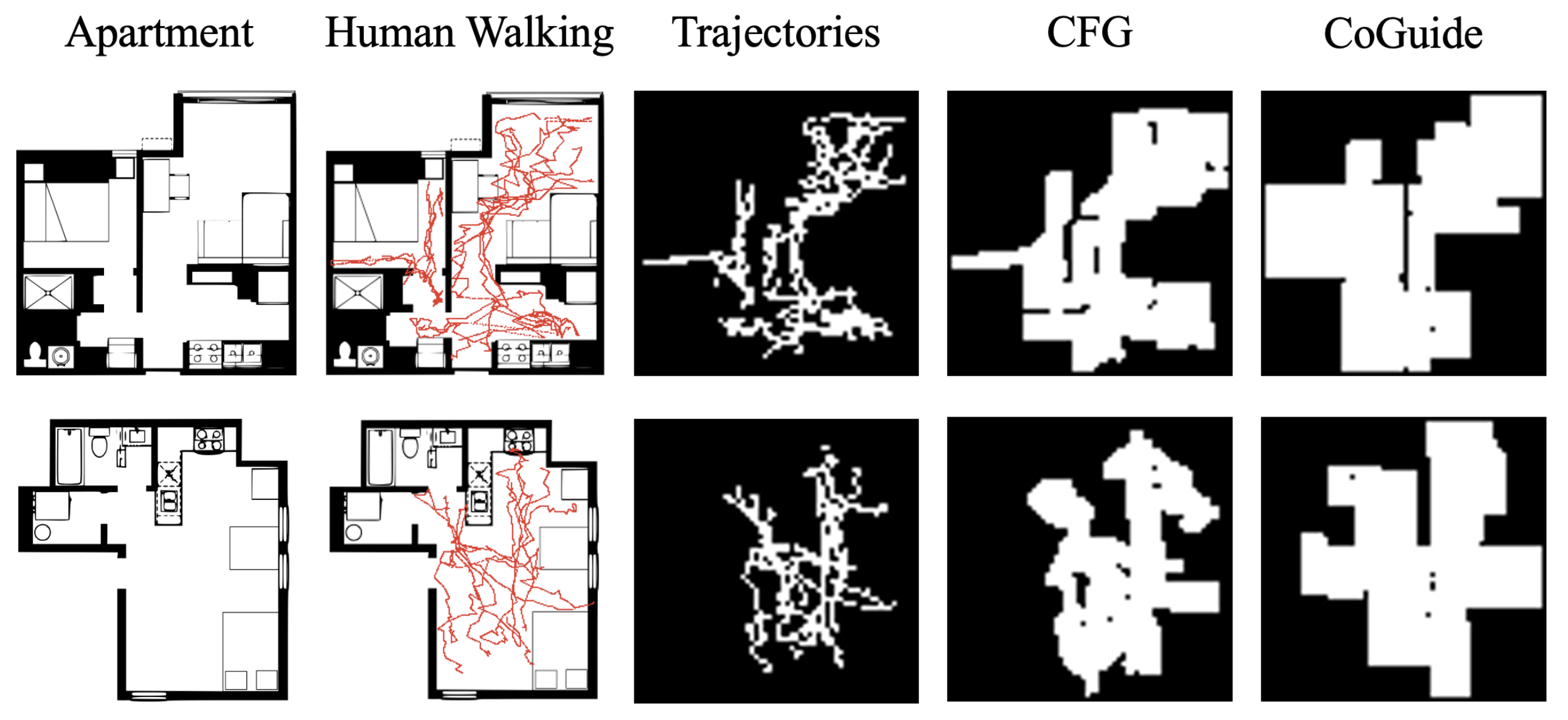

We also draw multiple samples from the posterior and compute the variance of the distance transform (with small translation tolerance) to estimate spatial uncertainty (see fig below). As trajectory density increases (across rows), uncertainty shrinks (reduction in the amount of "redness"), highlighting where additional user-collected trajectories would be most informative in a user-in-the-loop setting.

Real-World Floorplan Results

To evaluate real-world performance, we collected trajectories in two student apartments using the Qorvo DWM3000 ultrawideband (UWB) module Qorvo (2021). The UWB system consists of multiple anchors statically placed at known 3D coordinates in the apartment. The user carries a beacon that periodically pings each anchor, allowing us to estimate the time-of-flight (ToF) to that anchor. Using the ToF to line-of-sight anchors and the known speed of light, we apply trilateration to estimate the user’s 3D position. We then project the 3D position onto the 2D floorplan to obtain walking trajectories. The UWB setup provides locations with a standard deviation of 10 cm. It is worth noting that the trajectories obtained via this method are sparser and distributed somewhat differently compared to our A*-generated dataset.

The figure below compares CoGuide and CFG on these real-world measurements. Although both methods make errors, CoGuide infers more wall segments and room structure, whereas CFG often misses or misplaces major walls. This gap is expected since CFG is trained to model the posterior density under synthetic A*-generated trajectories, and therefore struggles to generalize to sparser, differently distributed real-world data.

Audio Restoration Experiment

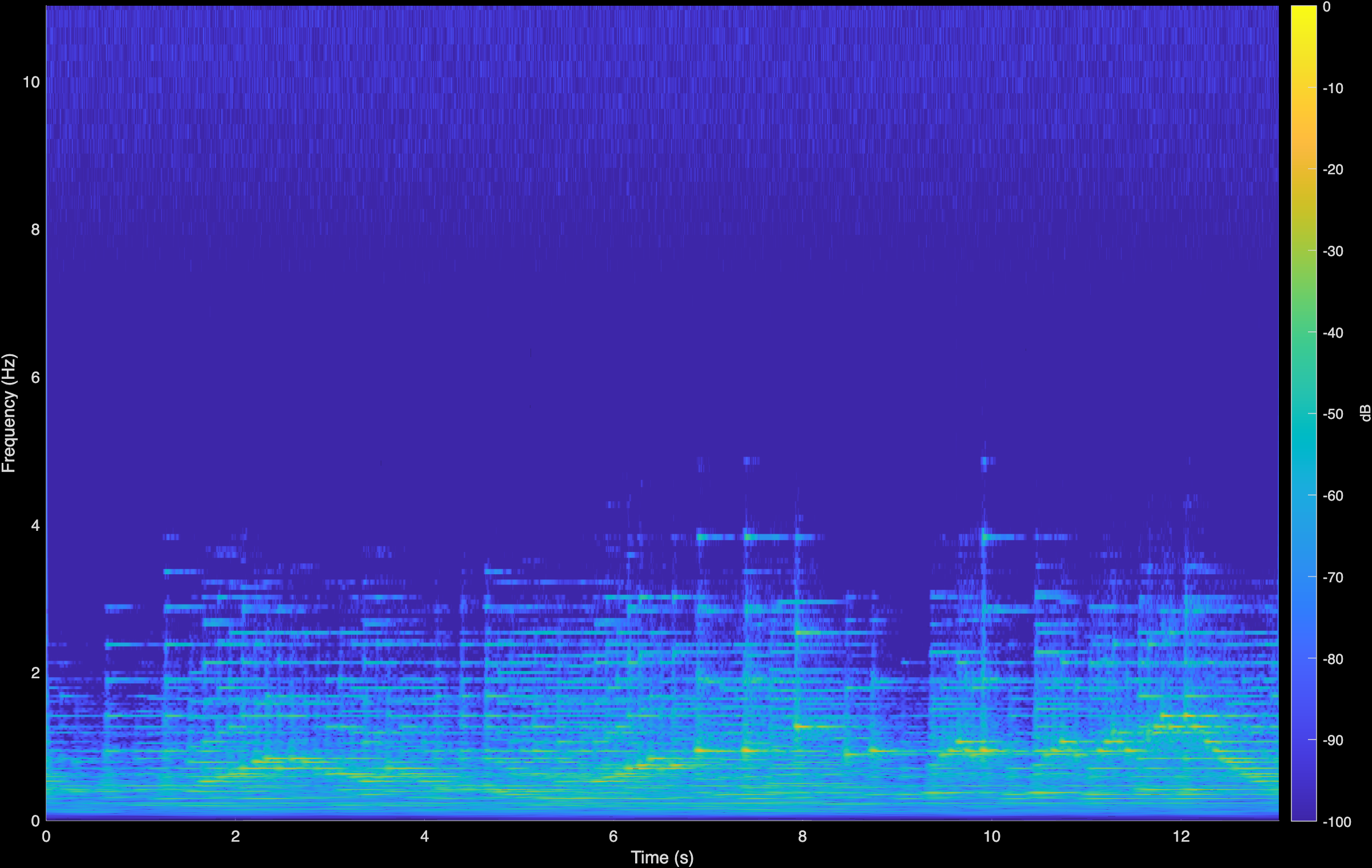

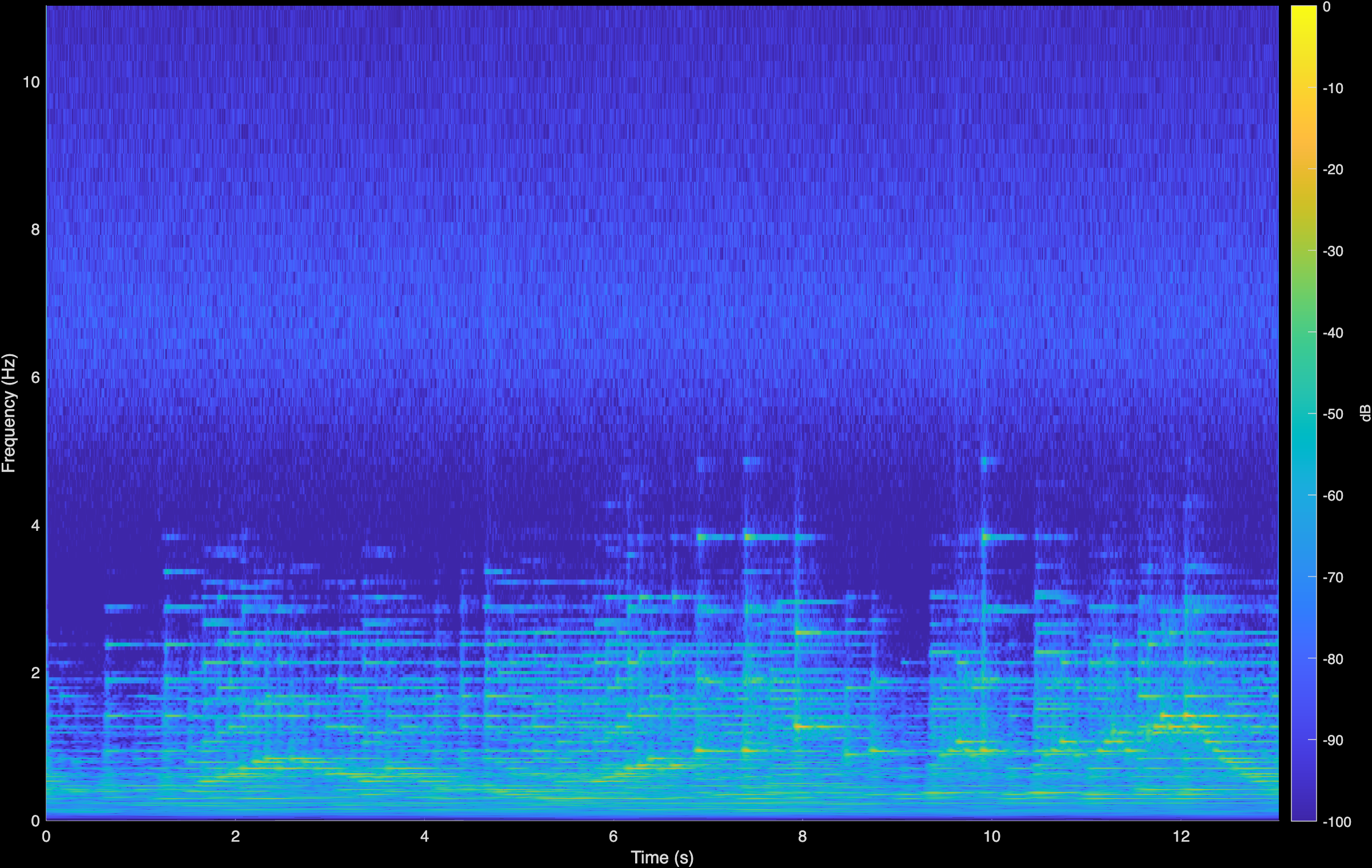

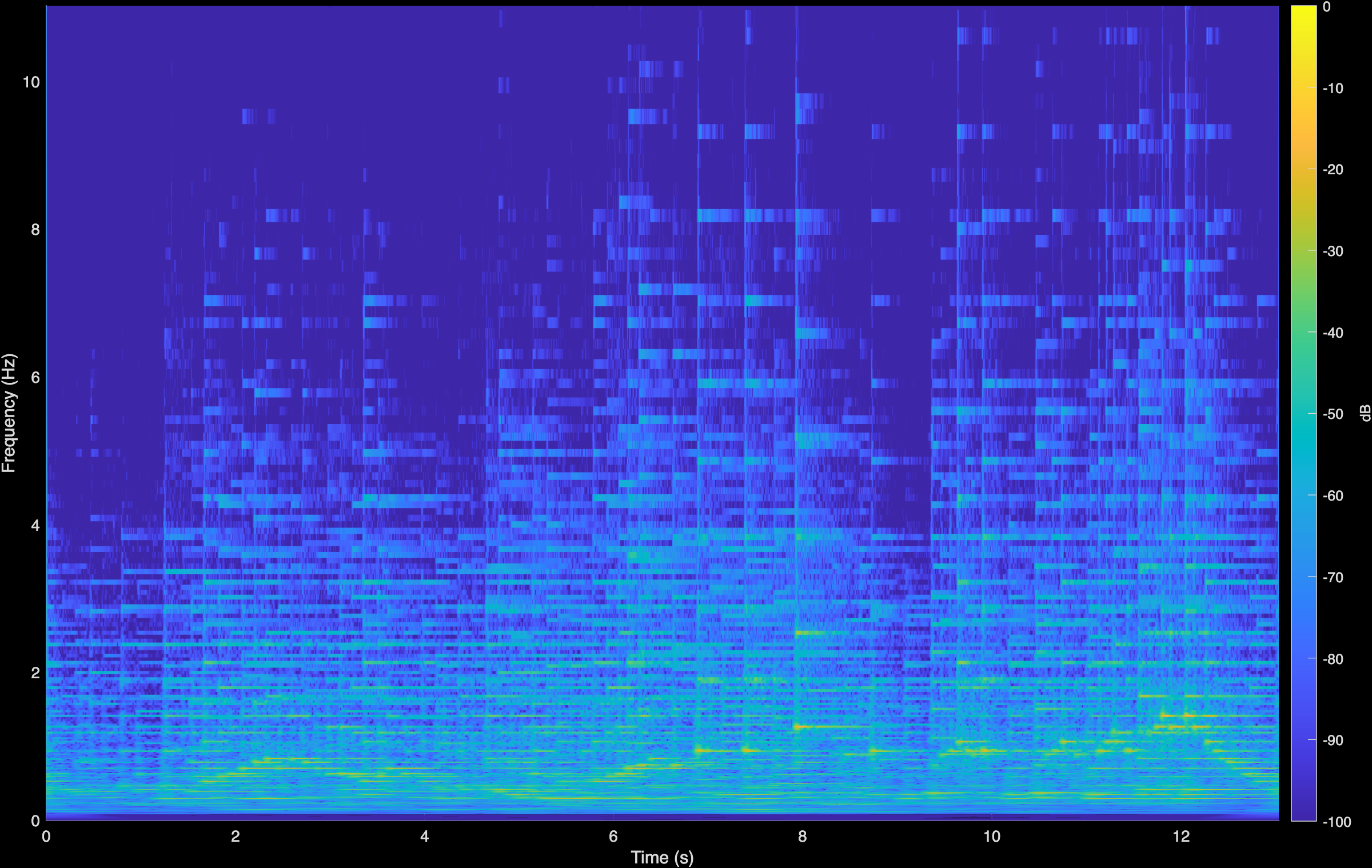

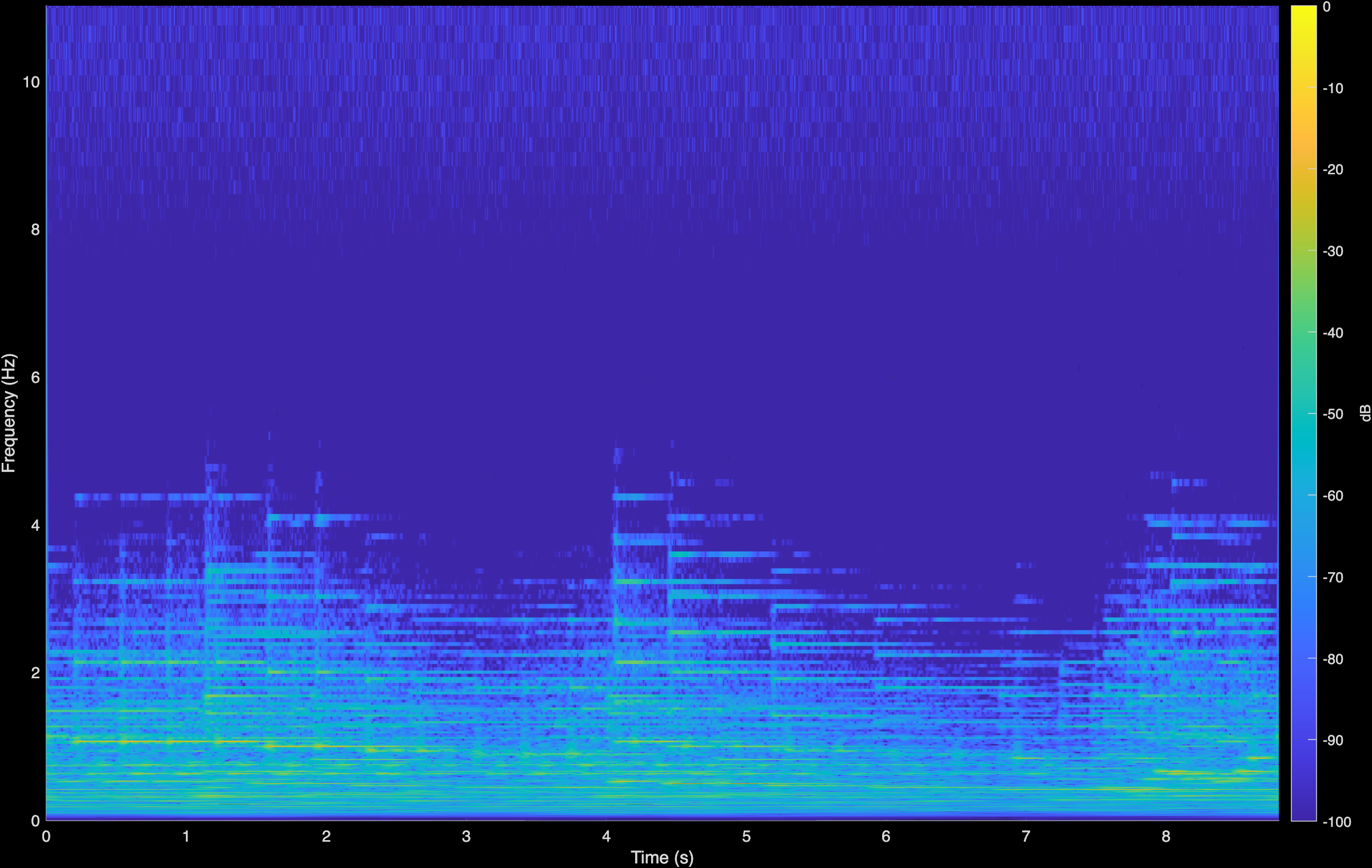

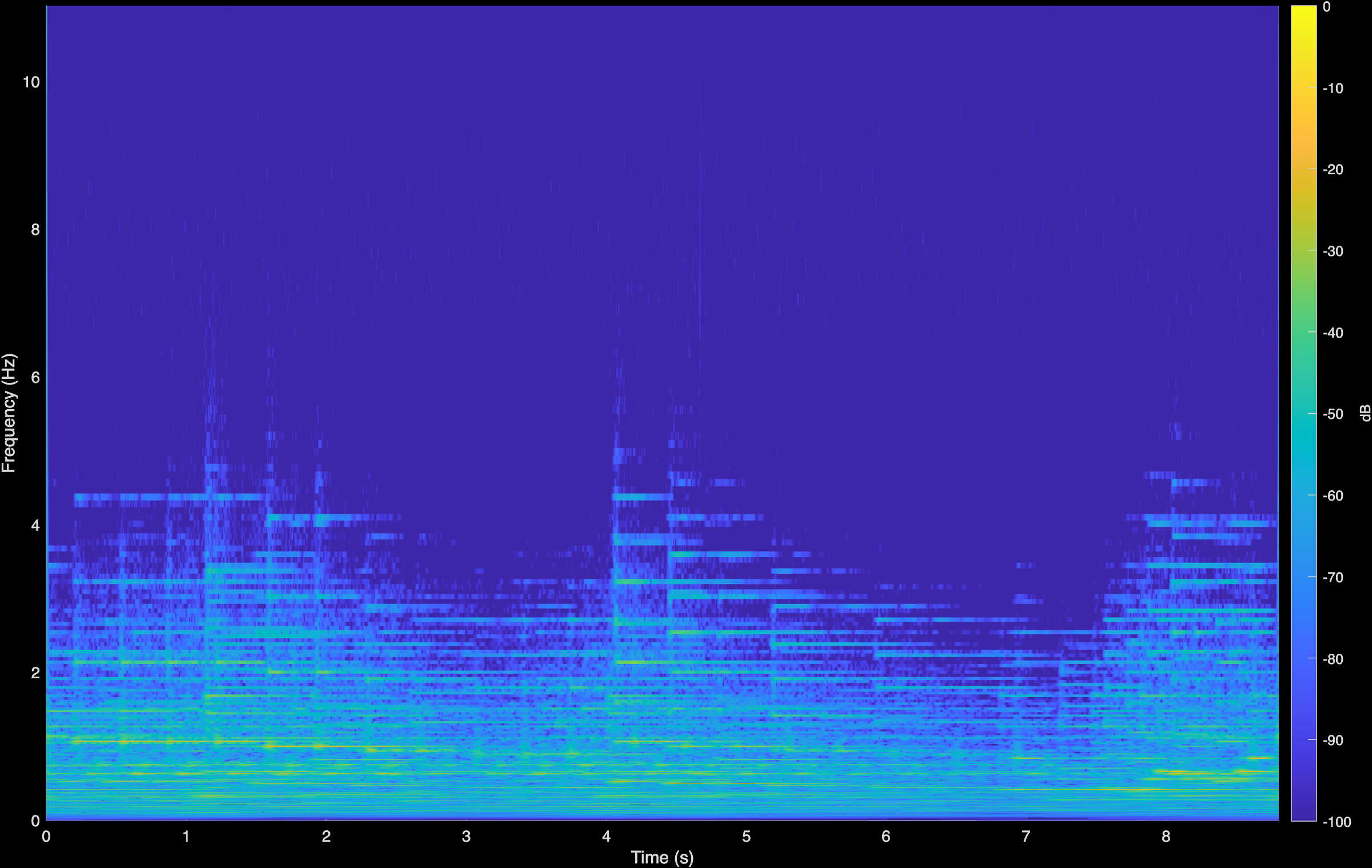

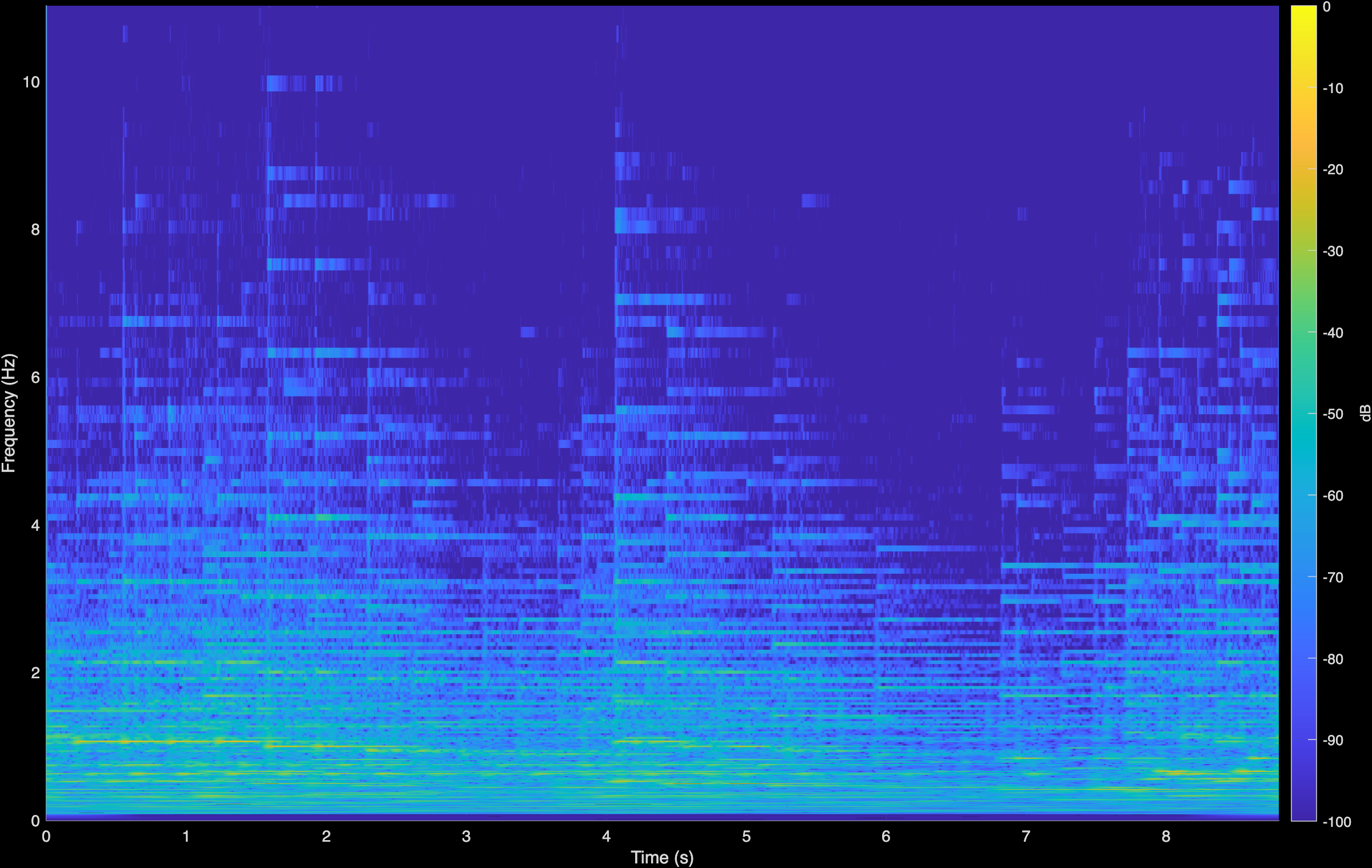

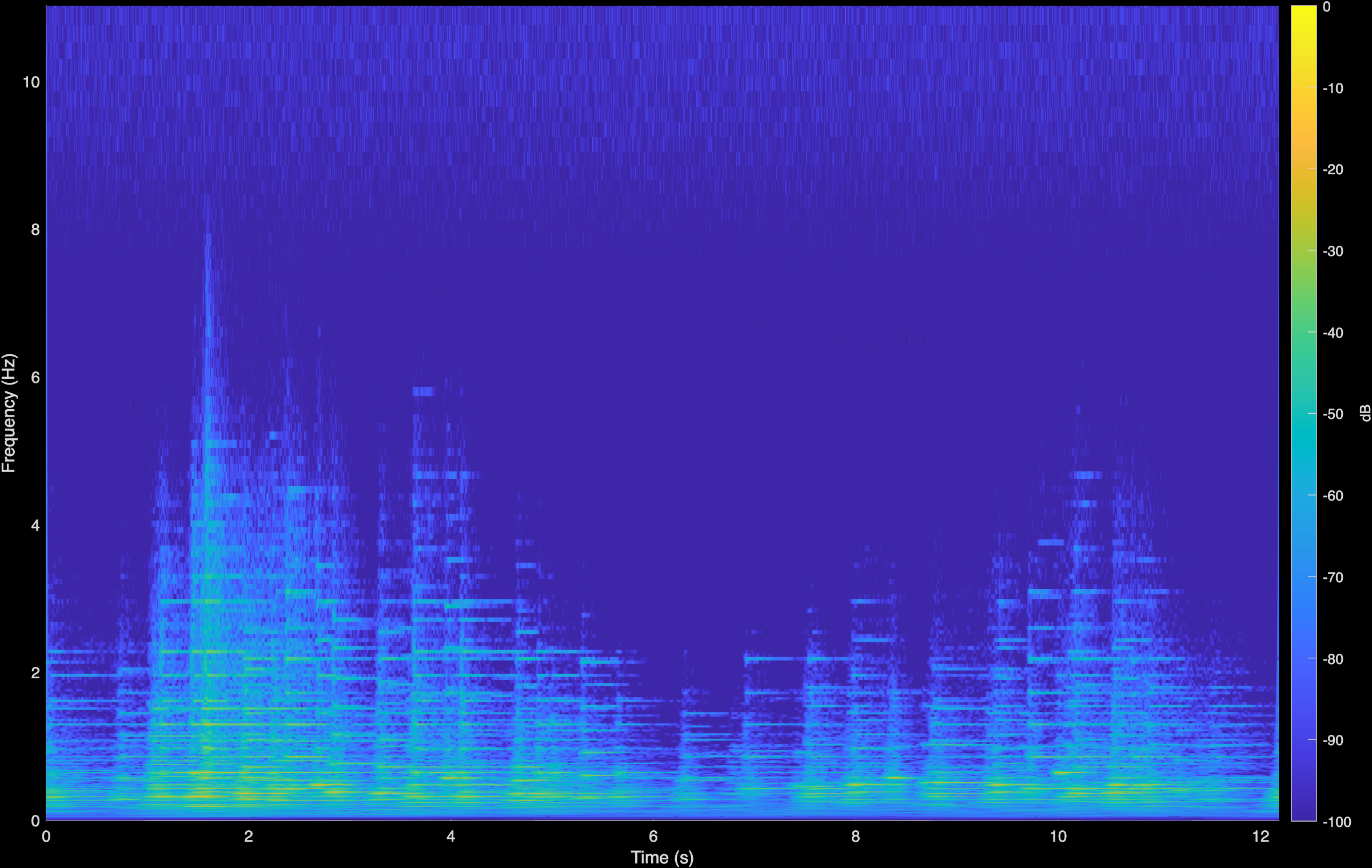

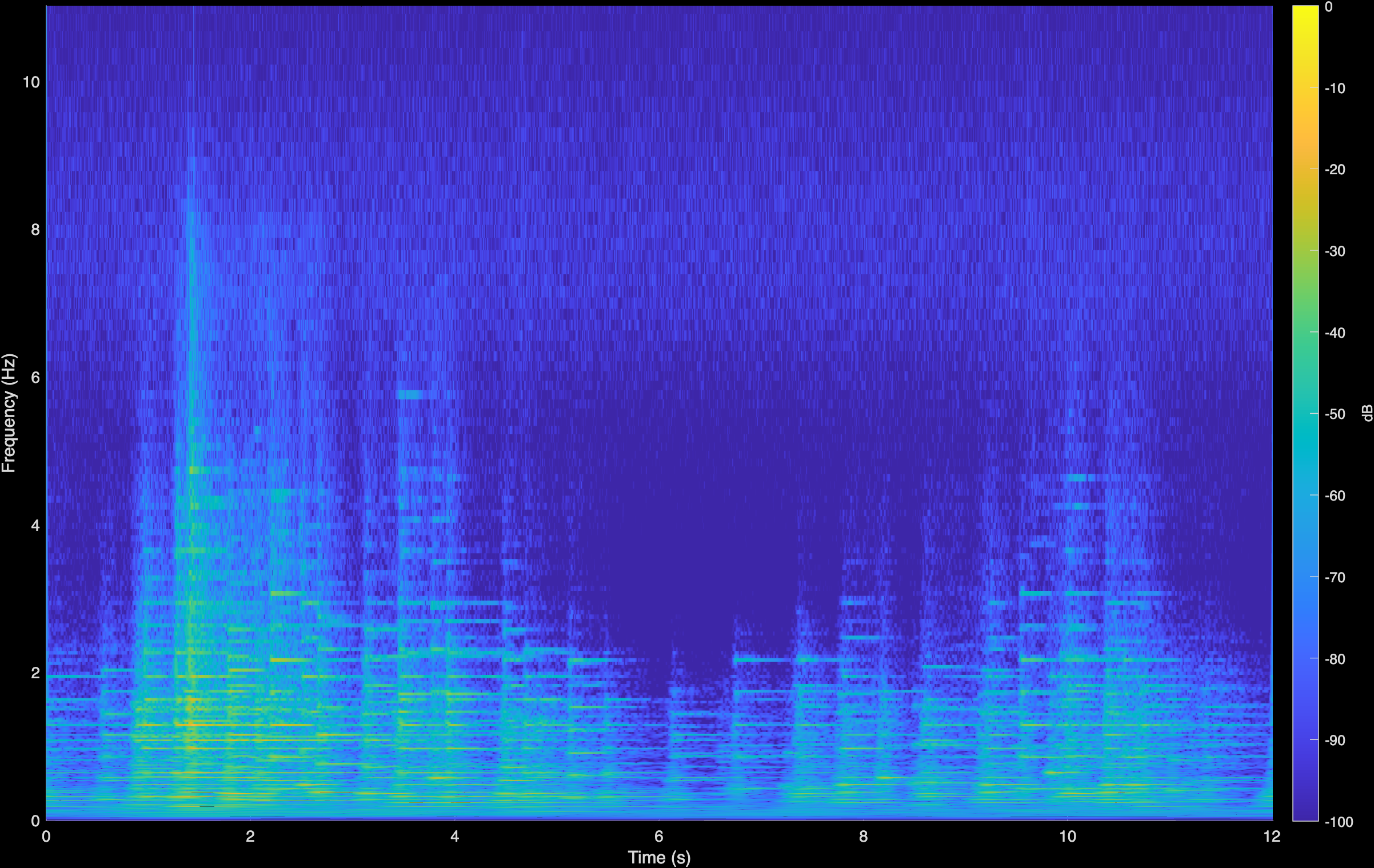

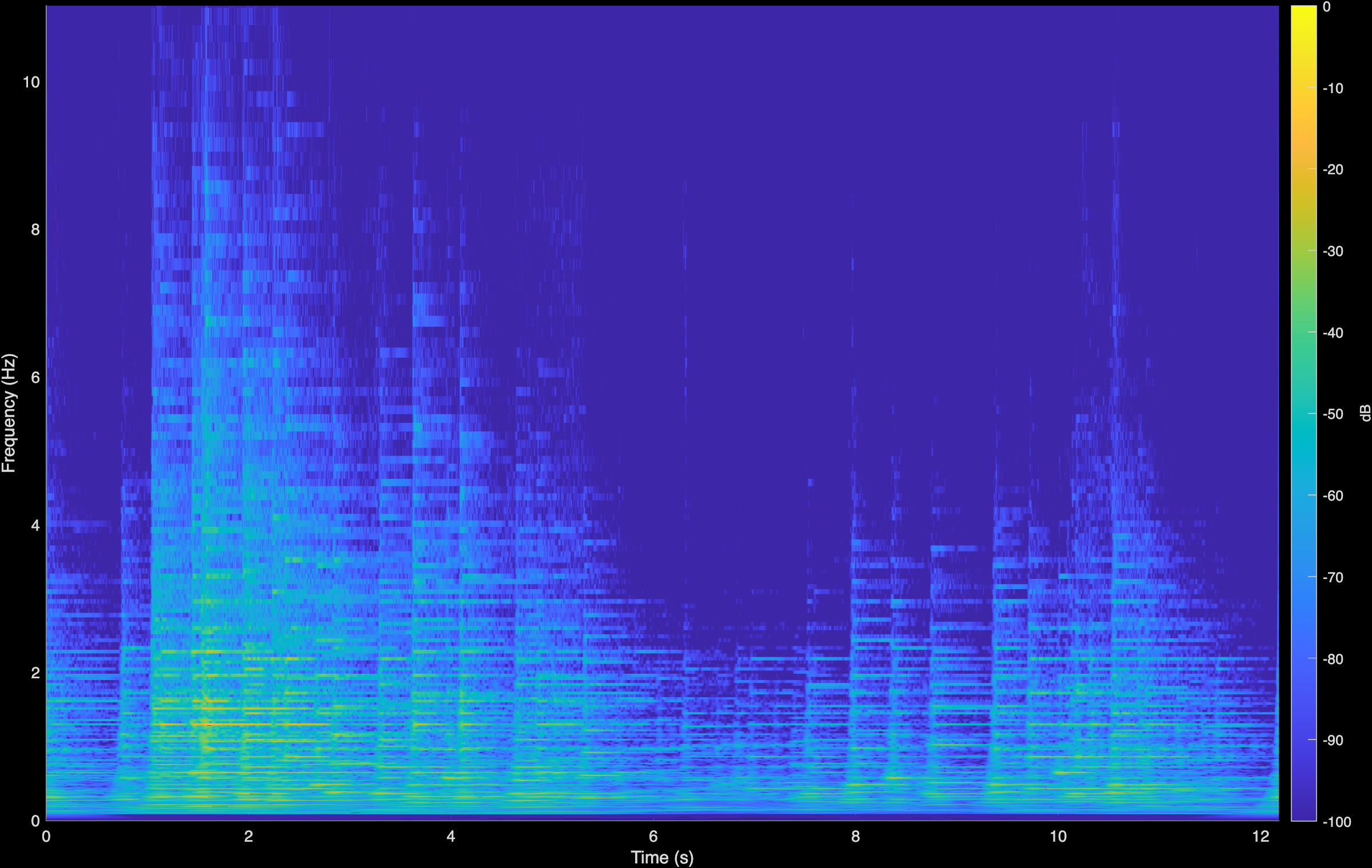

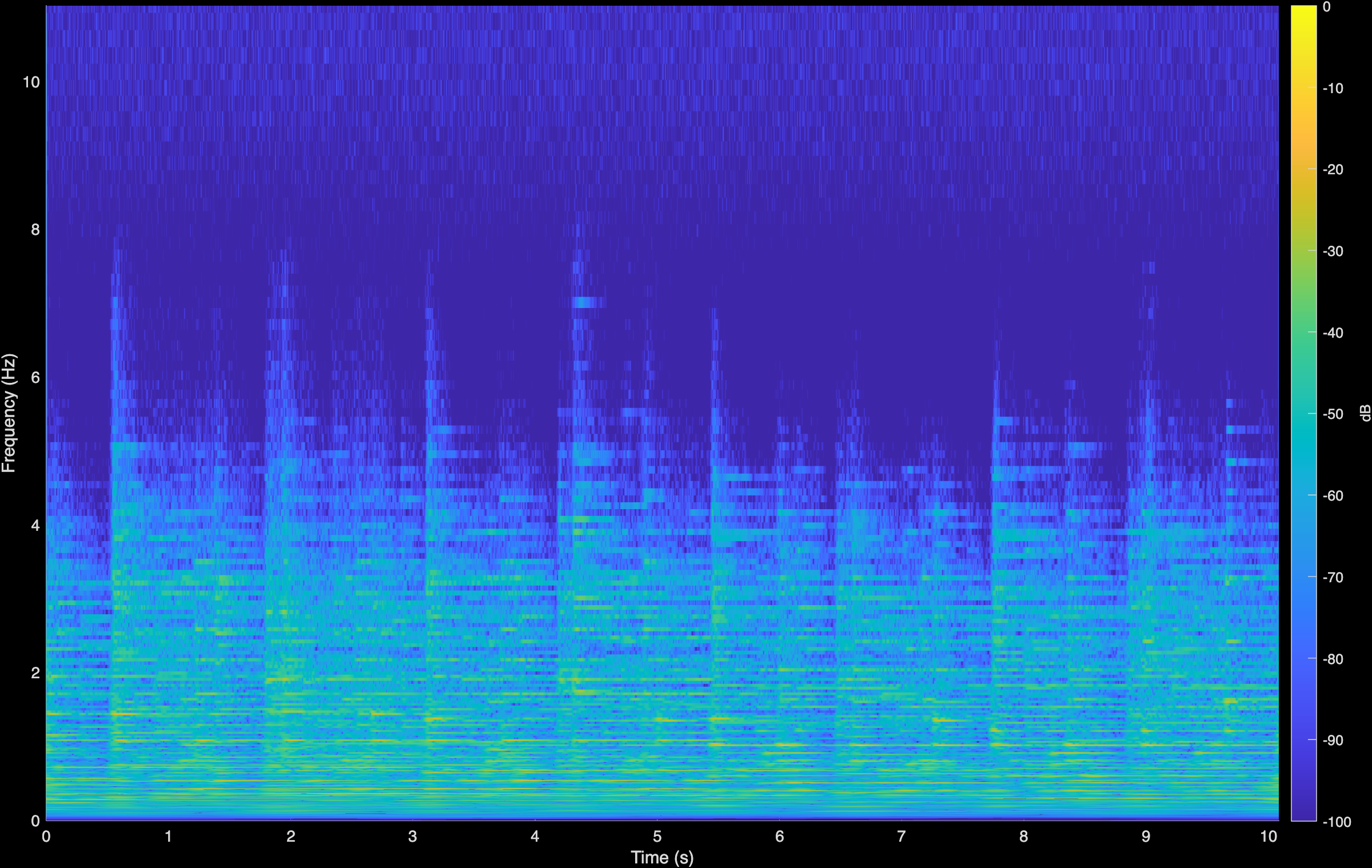

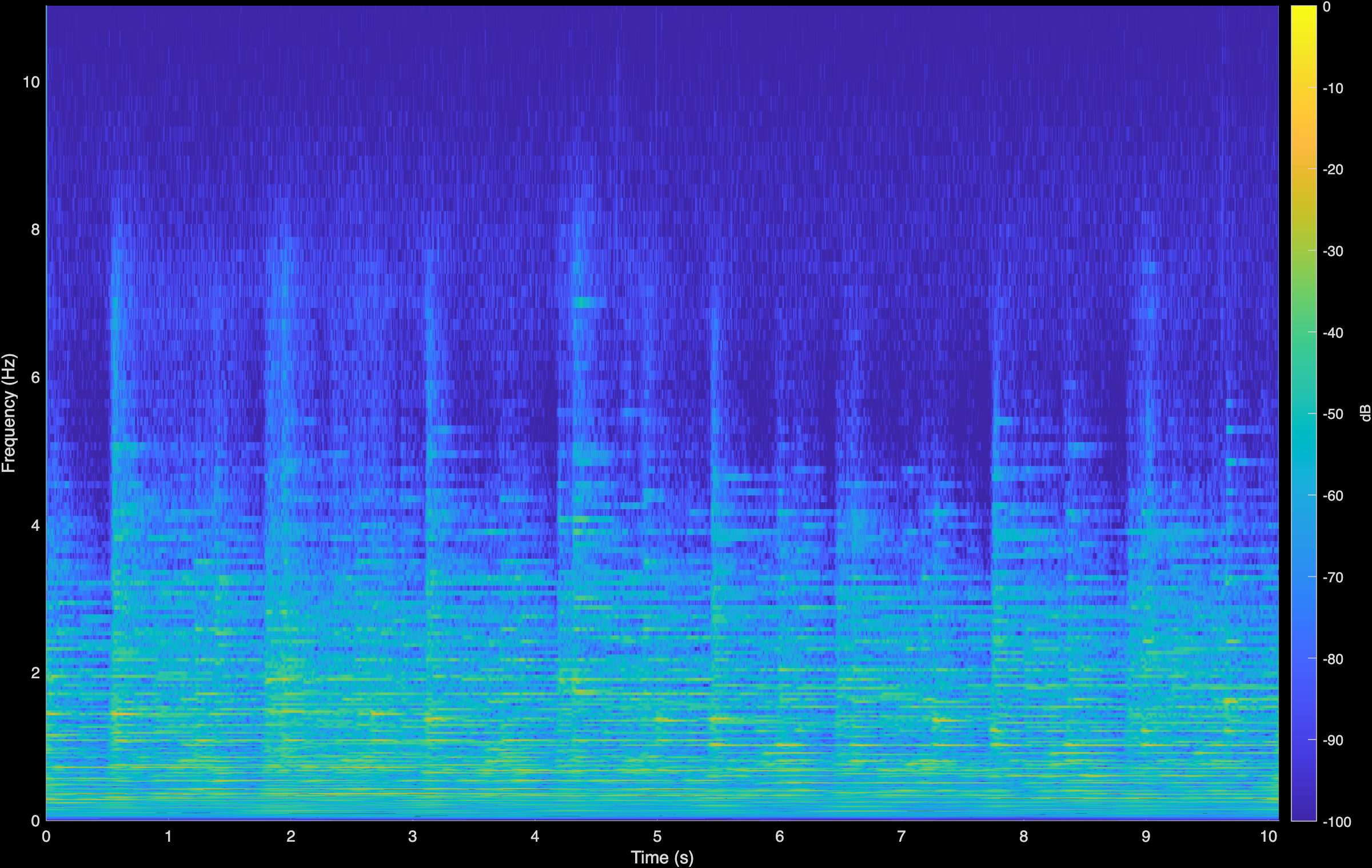

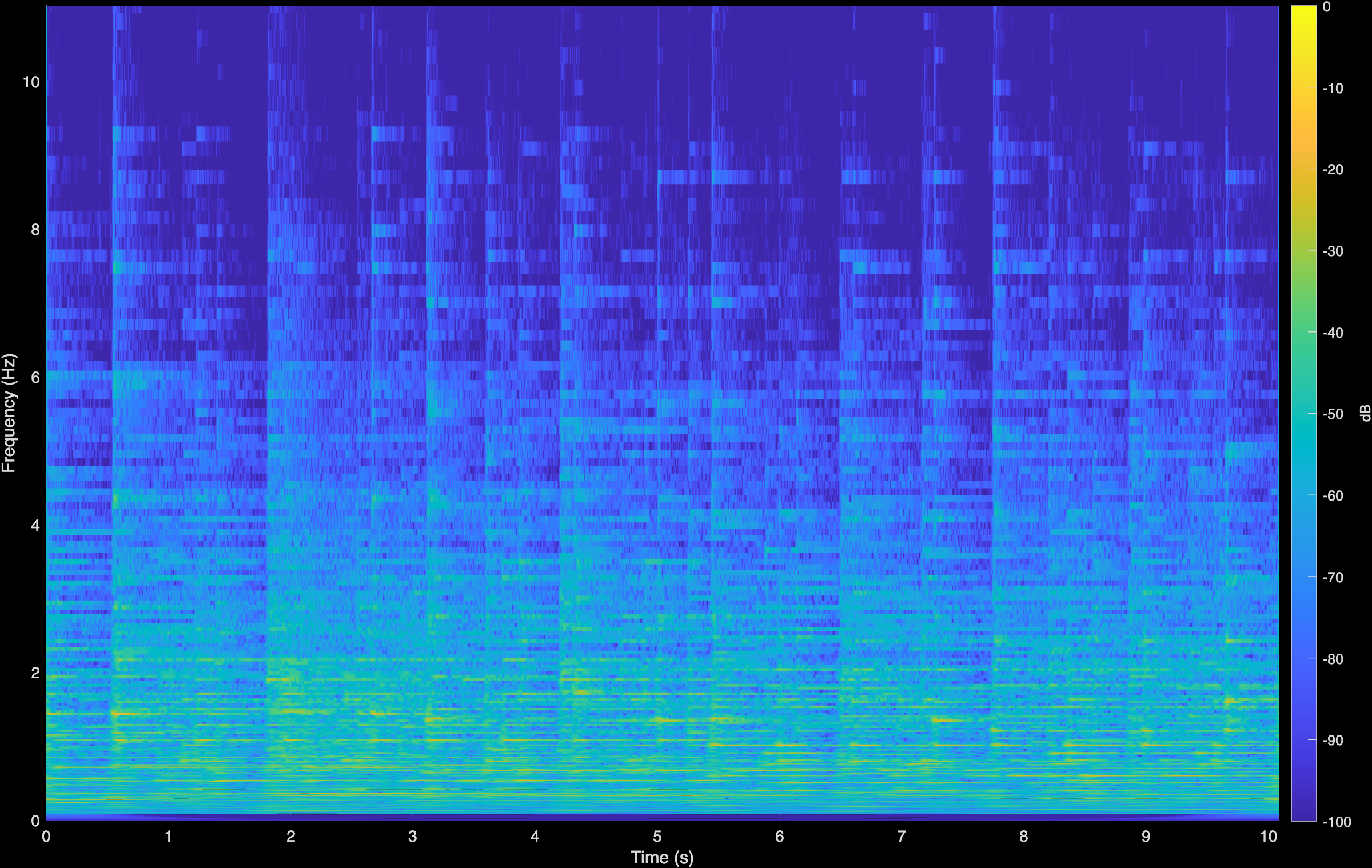

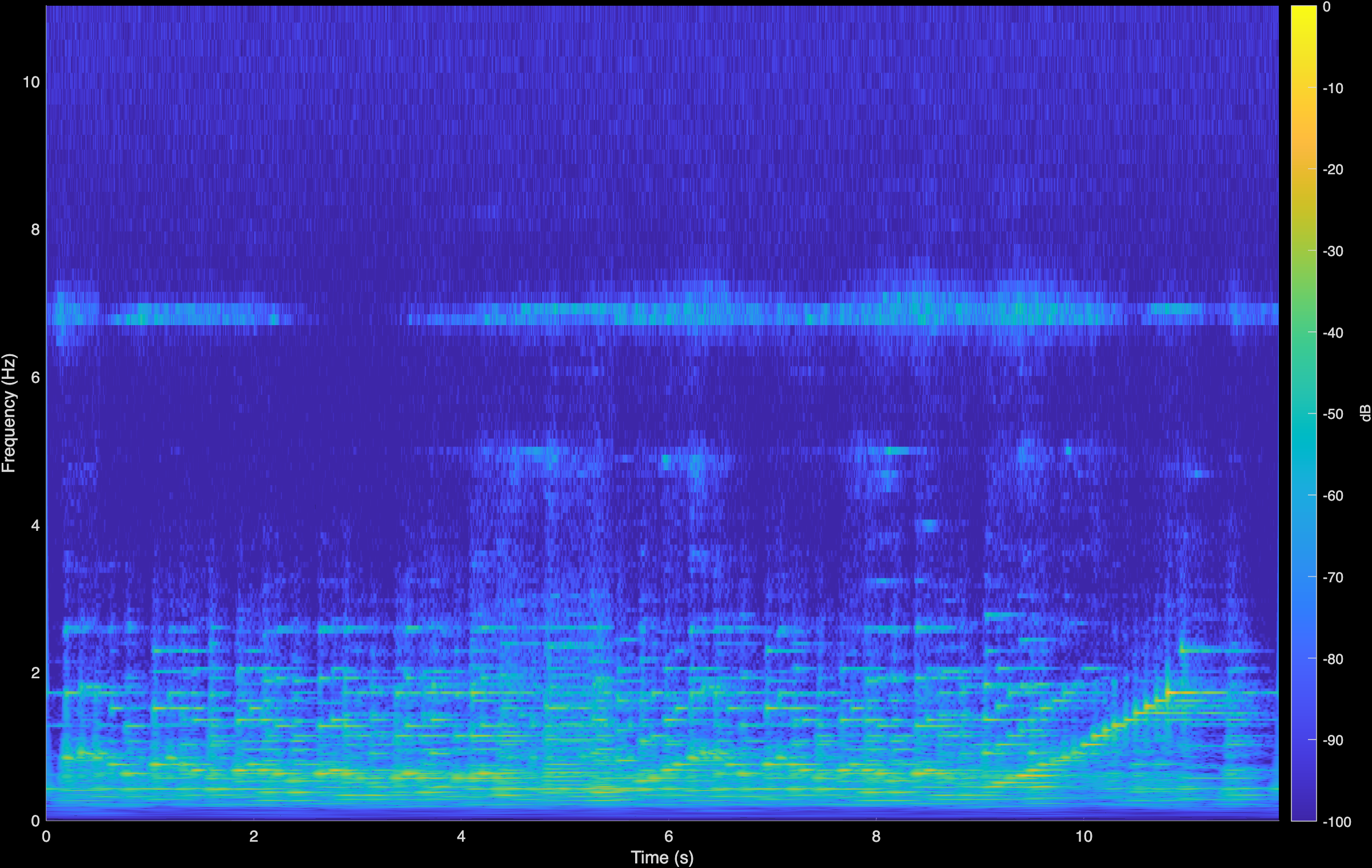

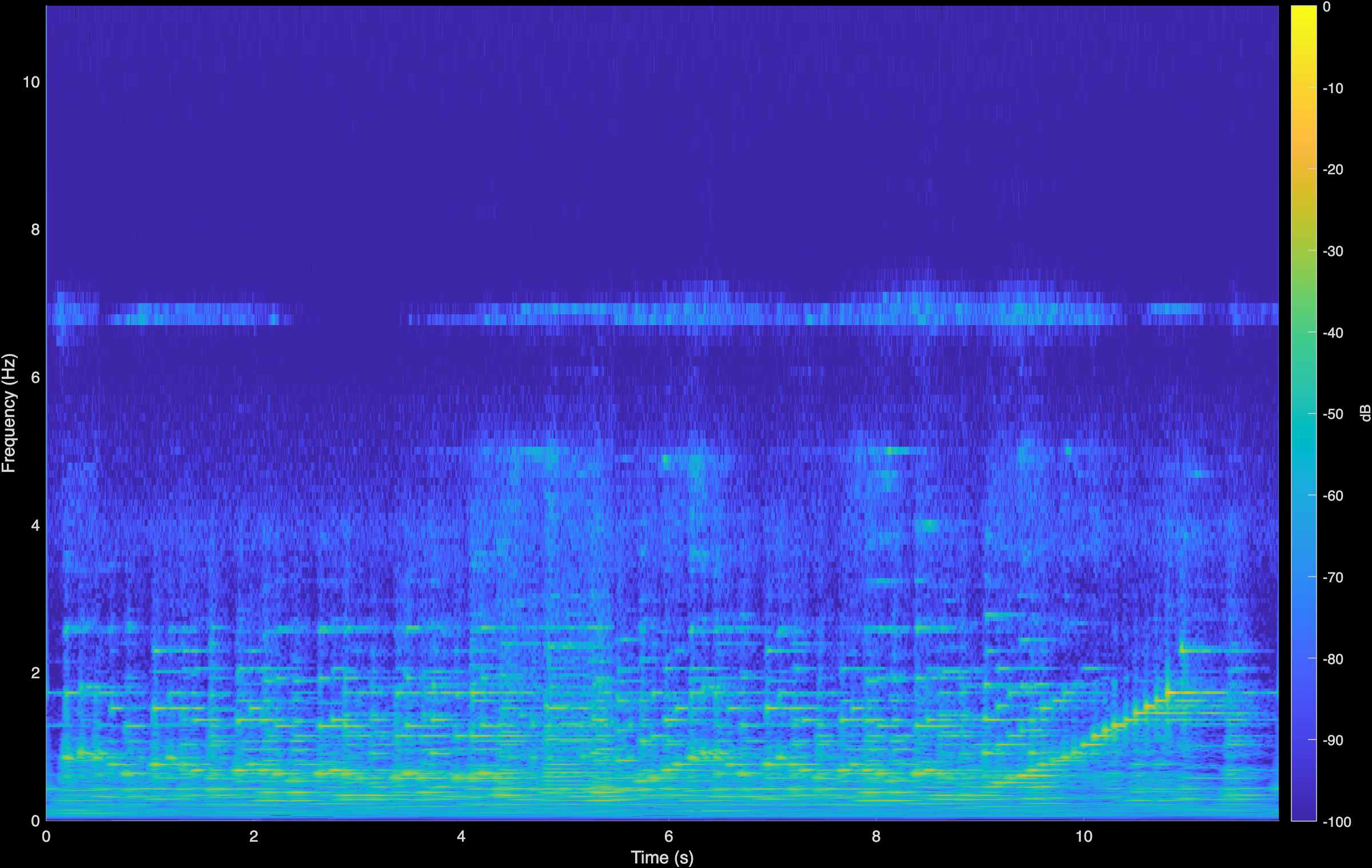

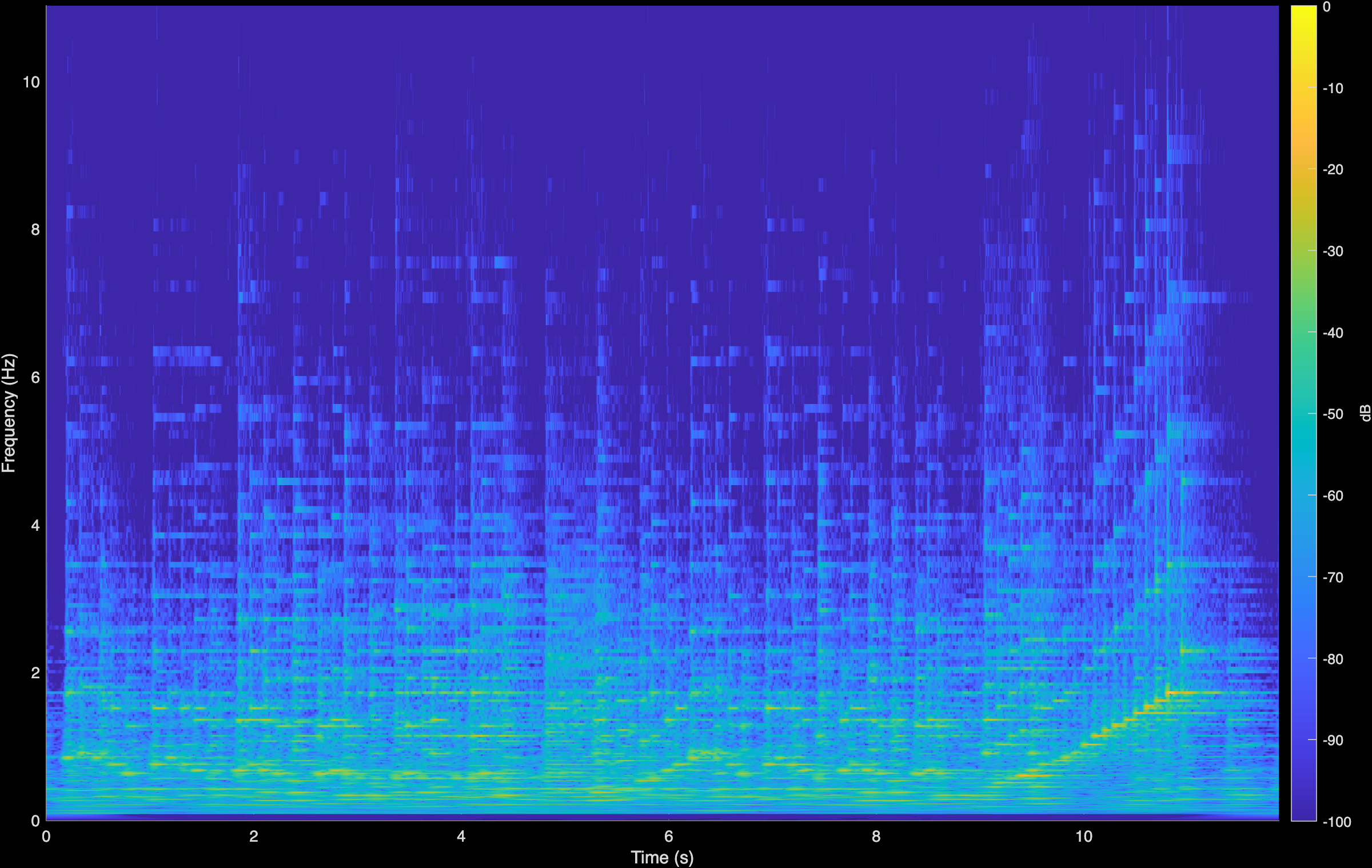

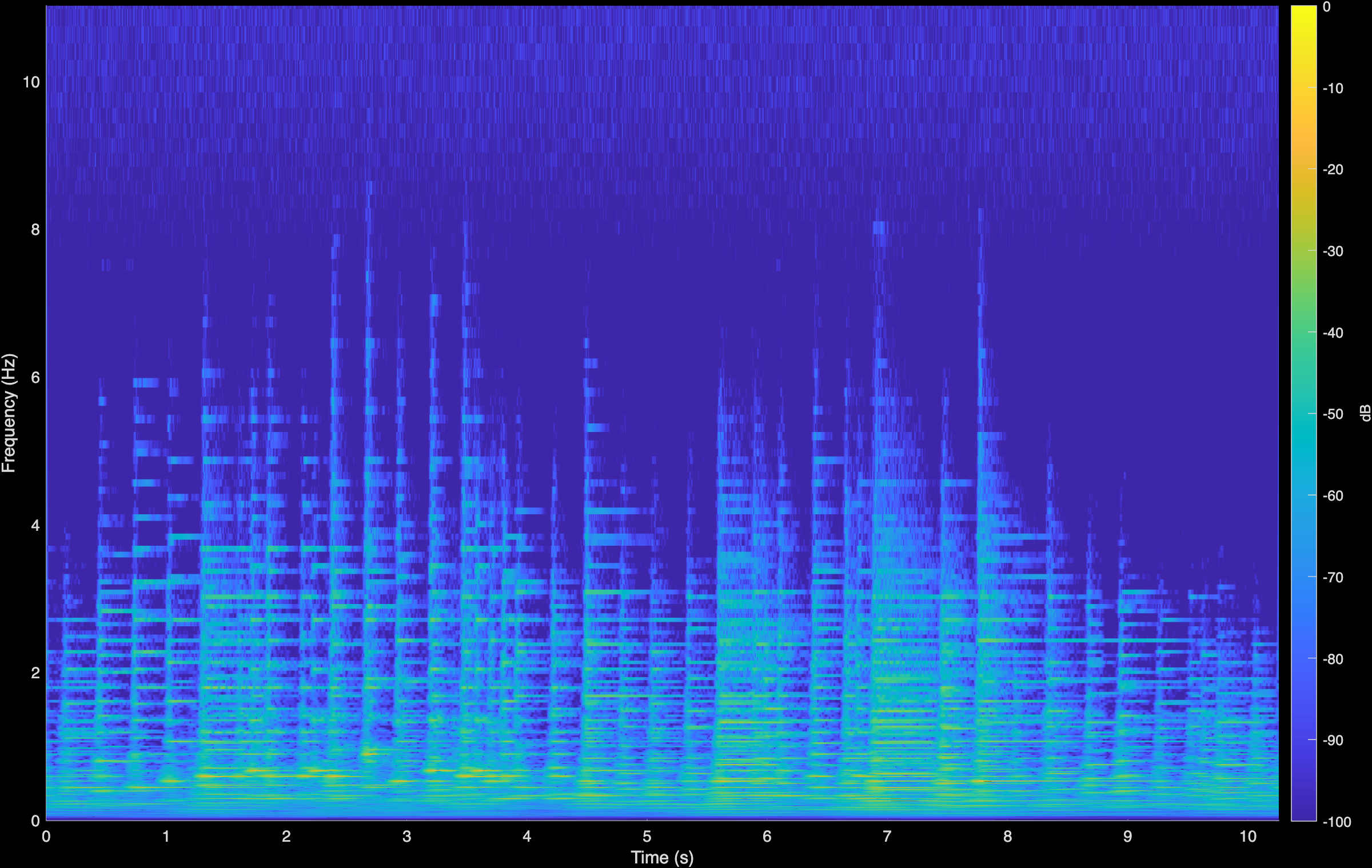

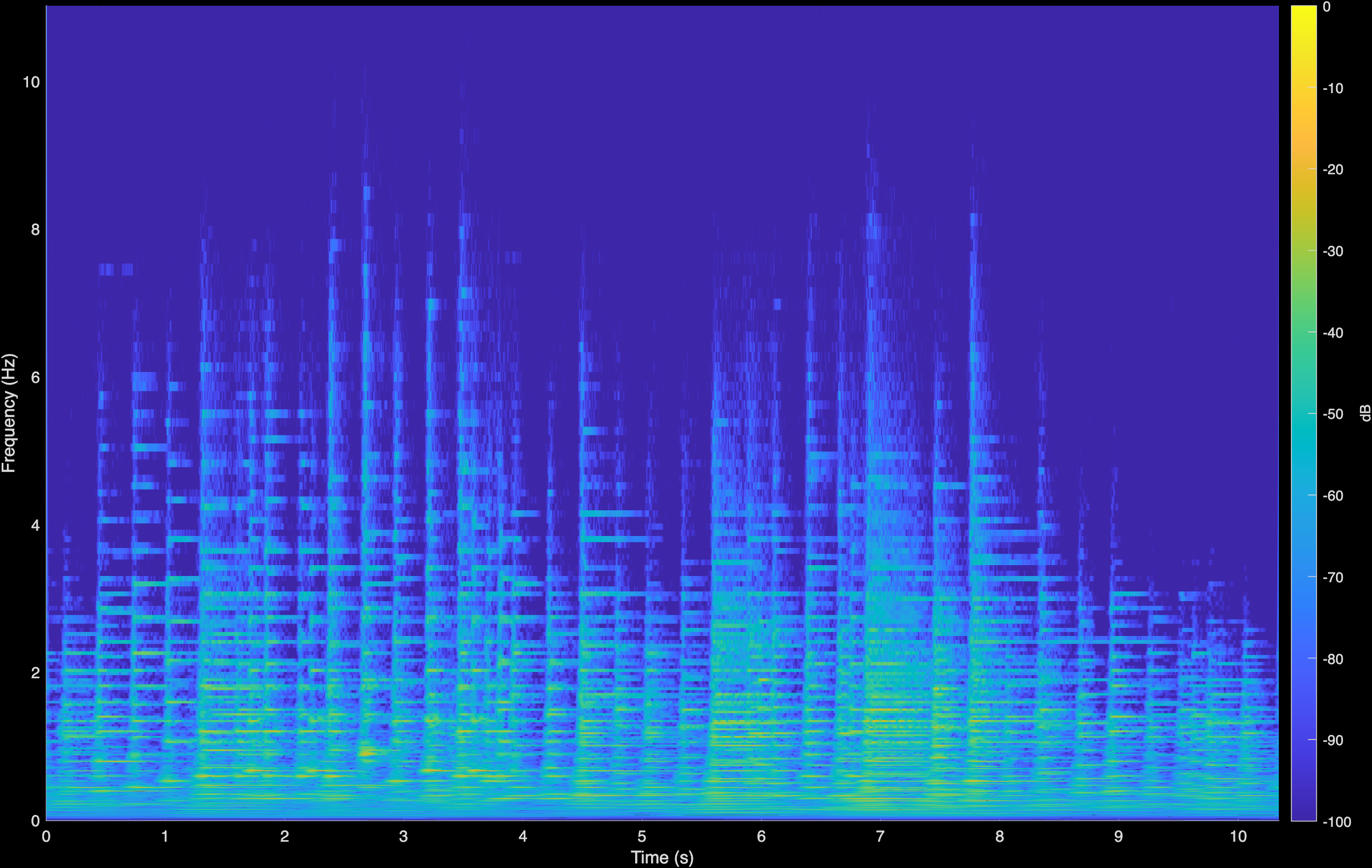

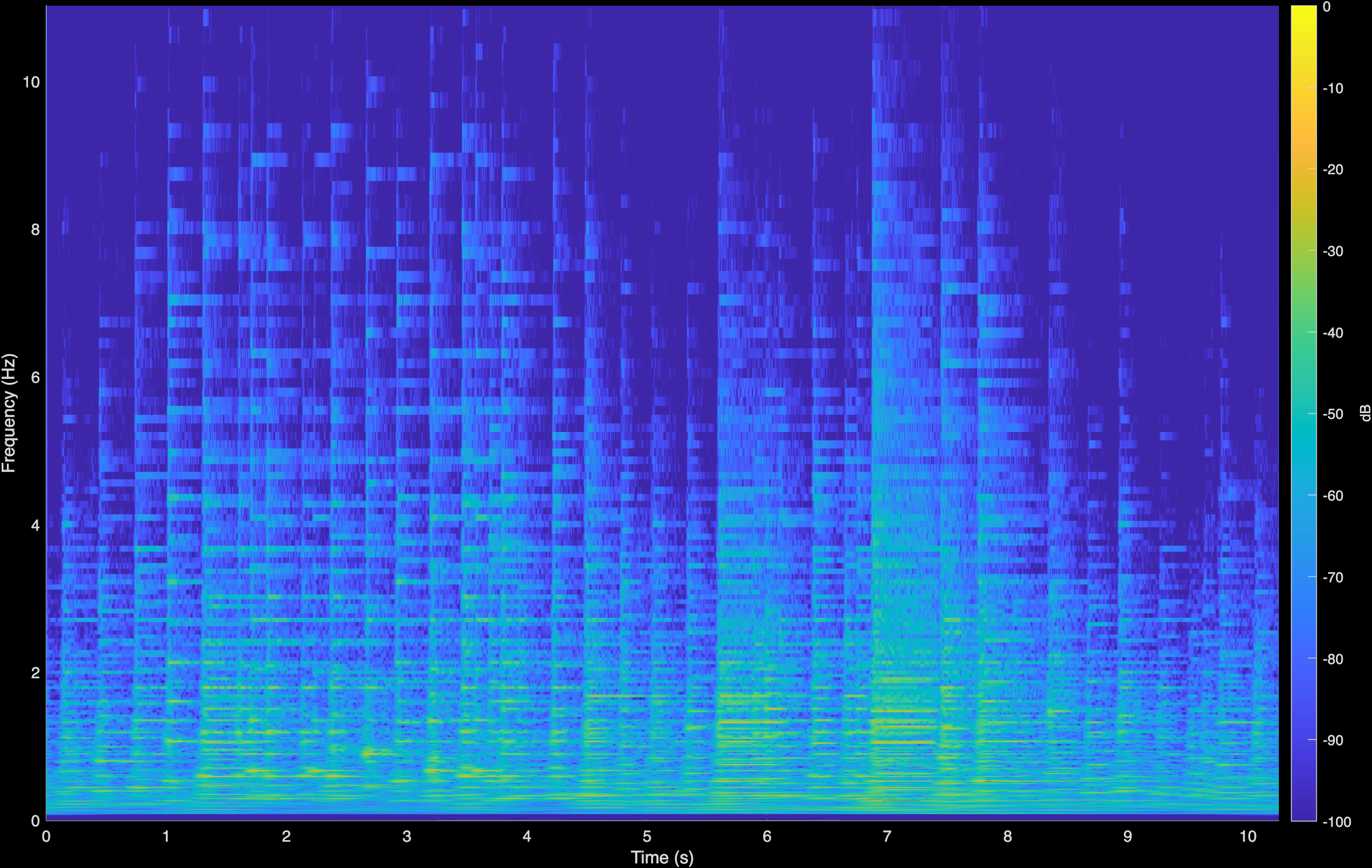

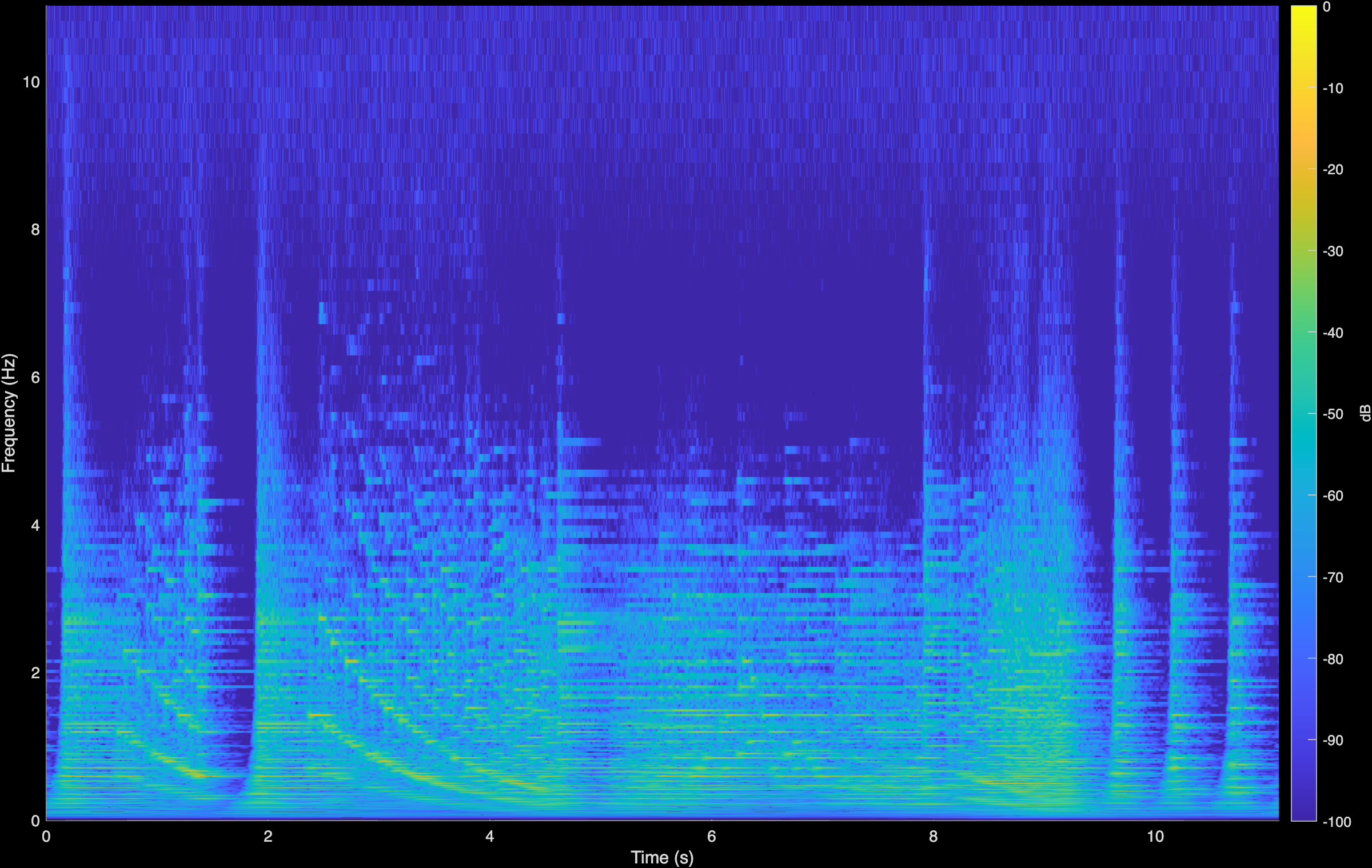

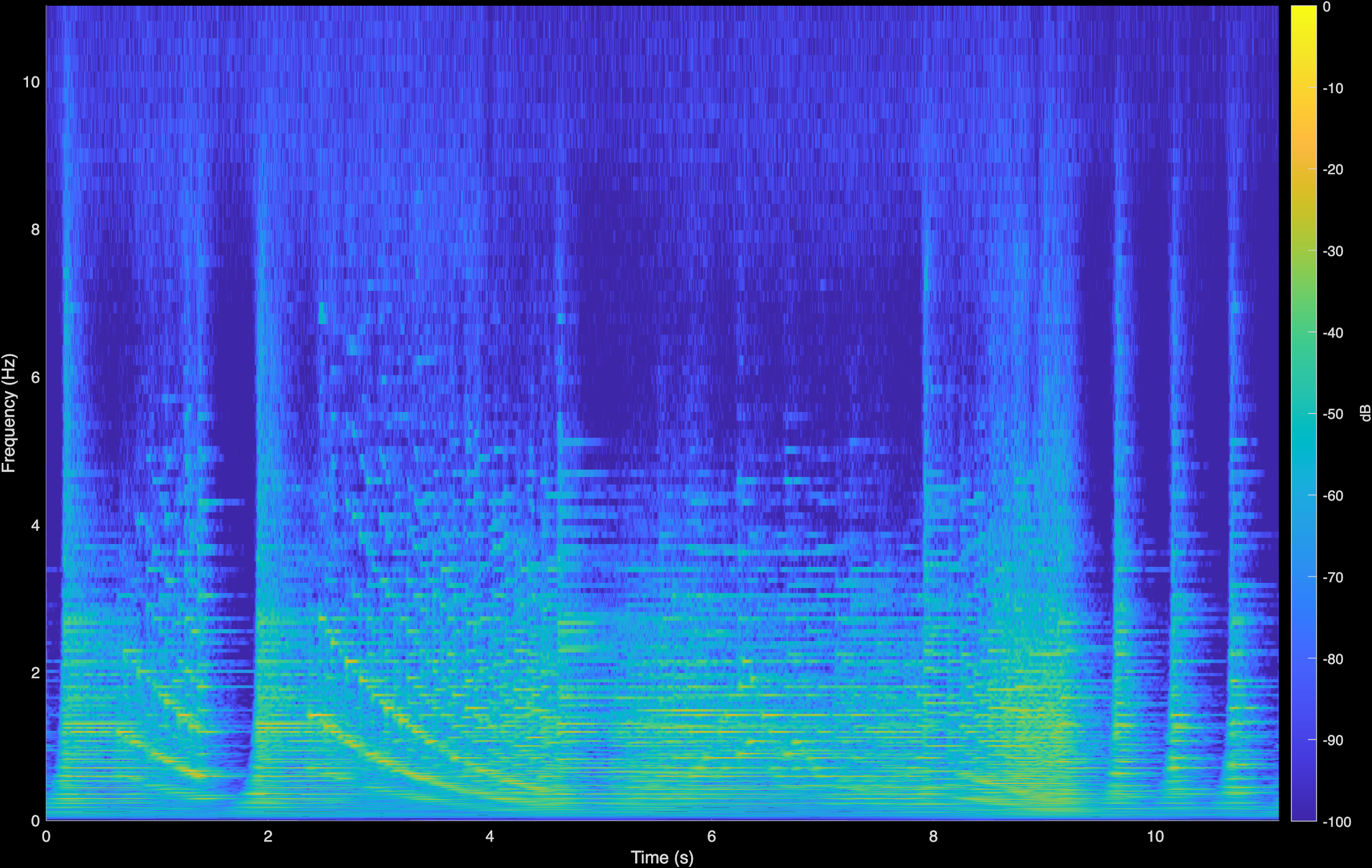

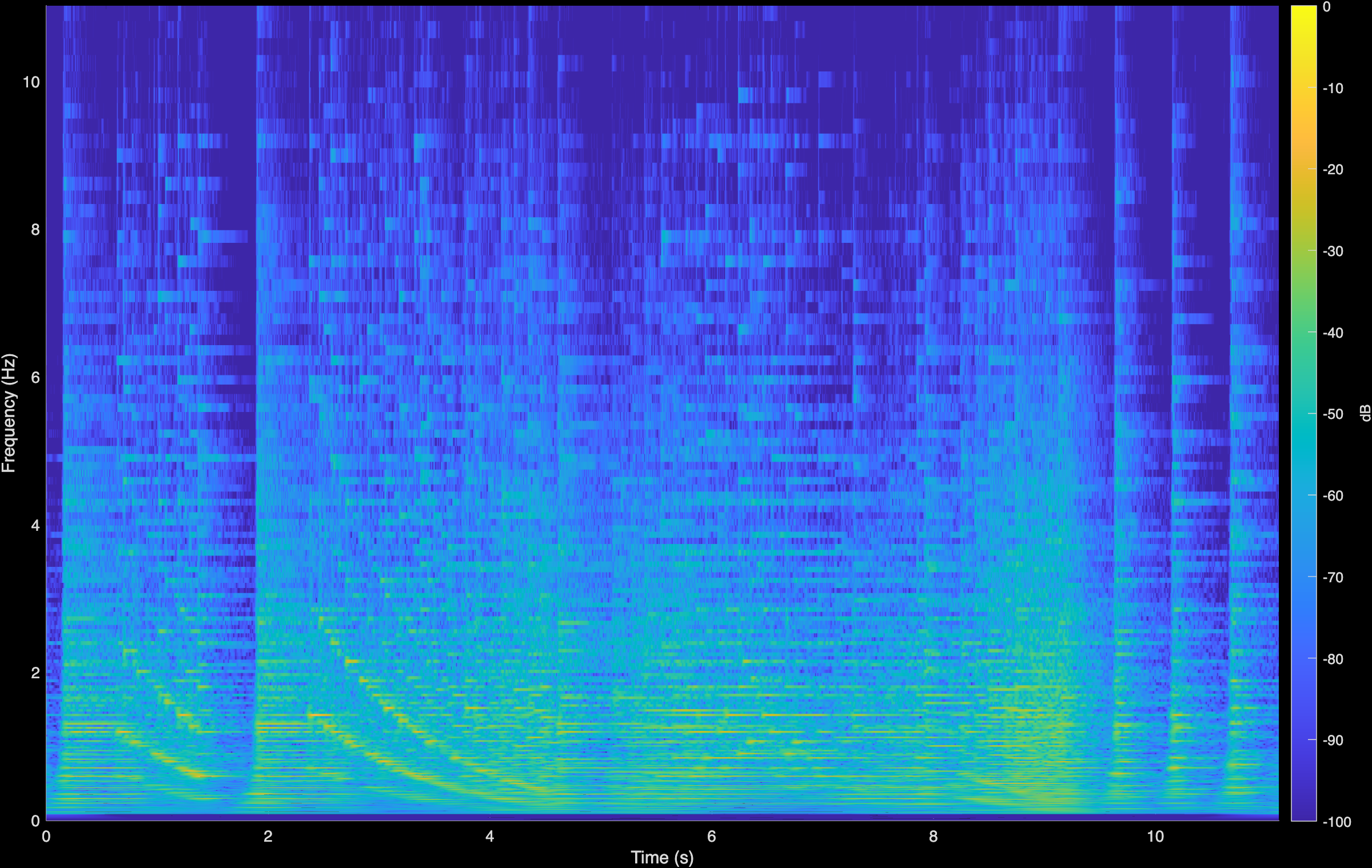

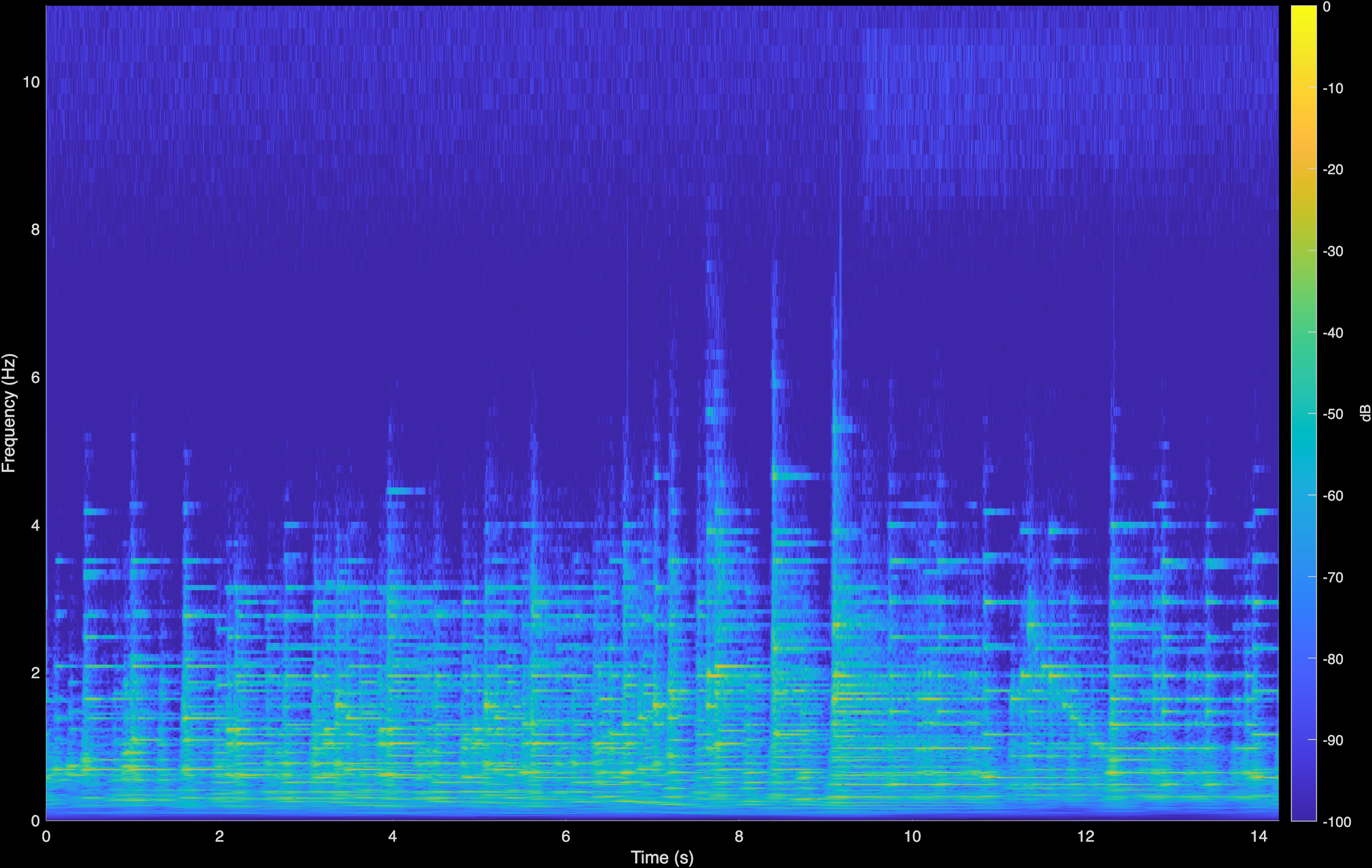

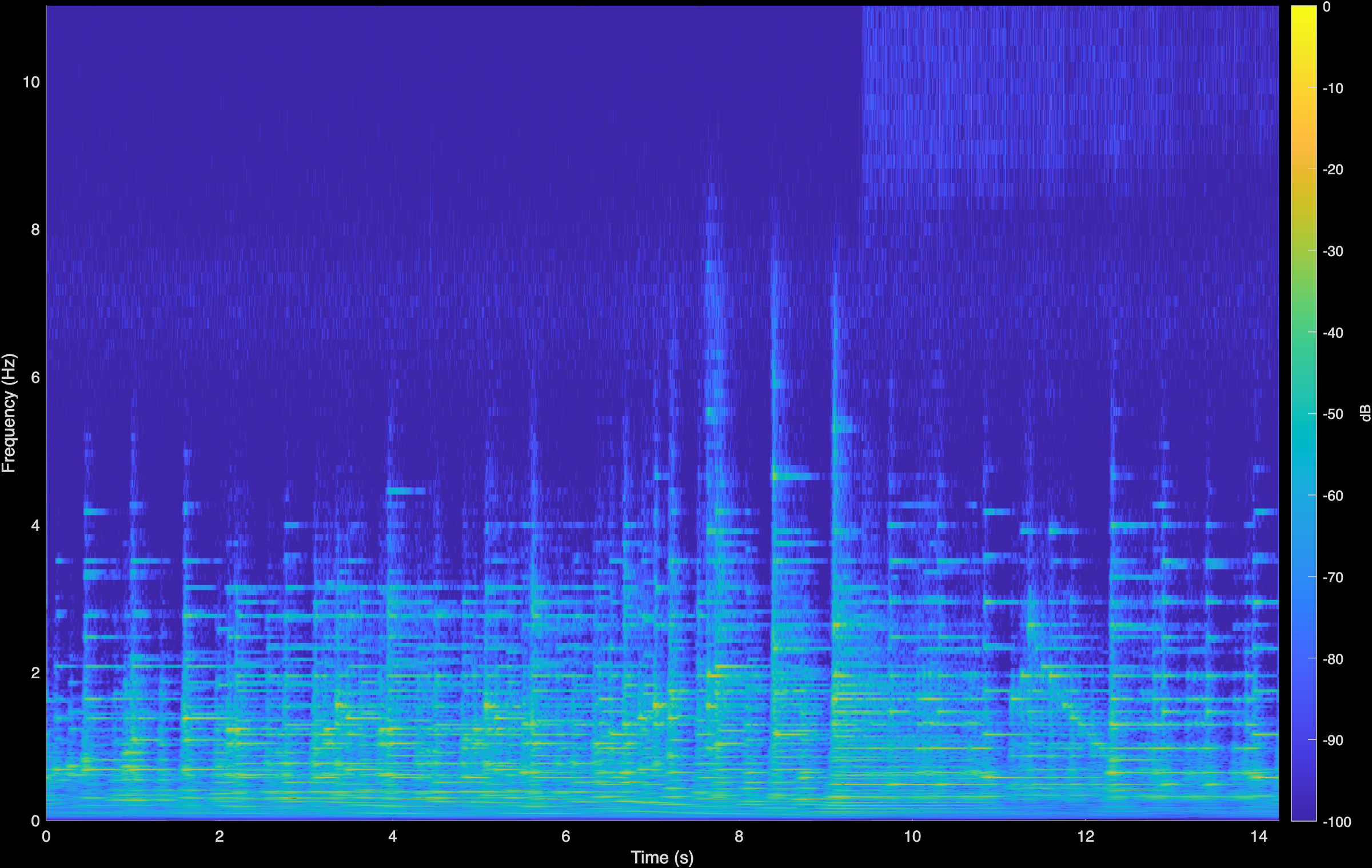

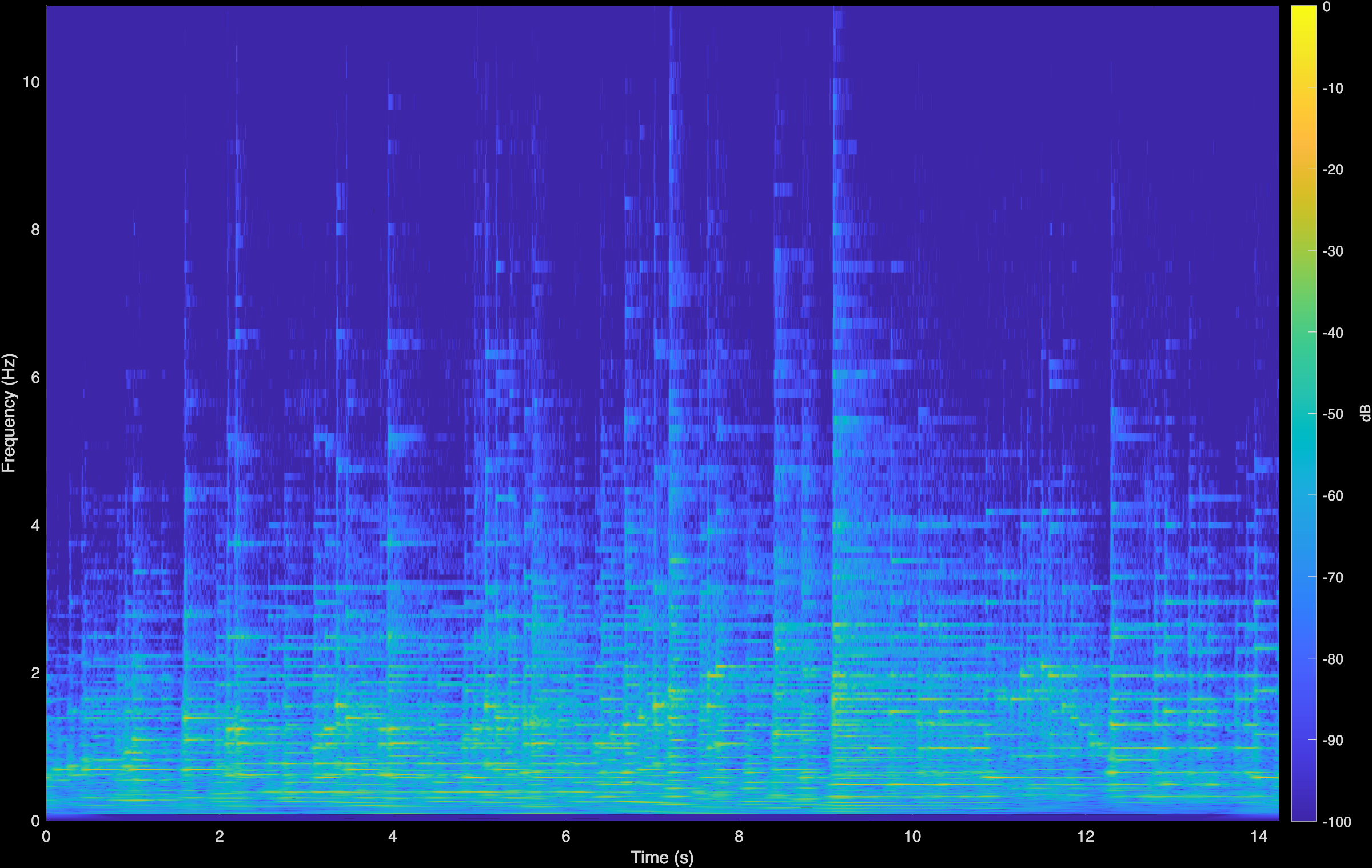

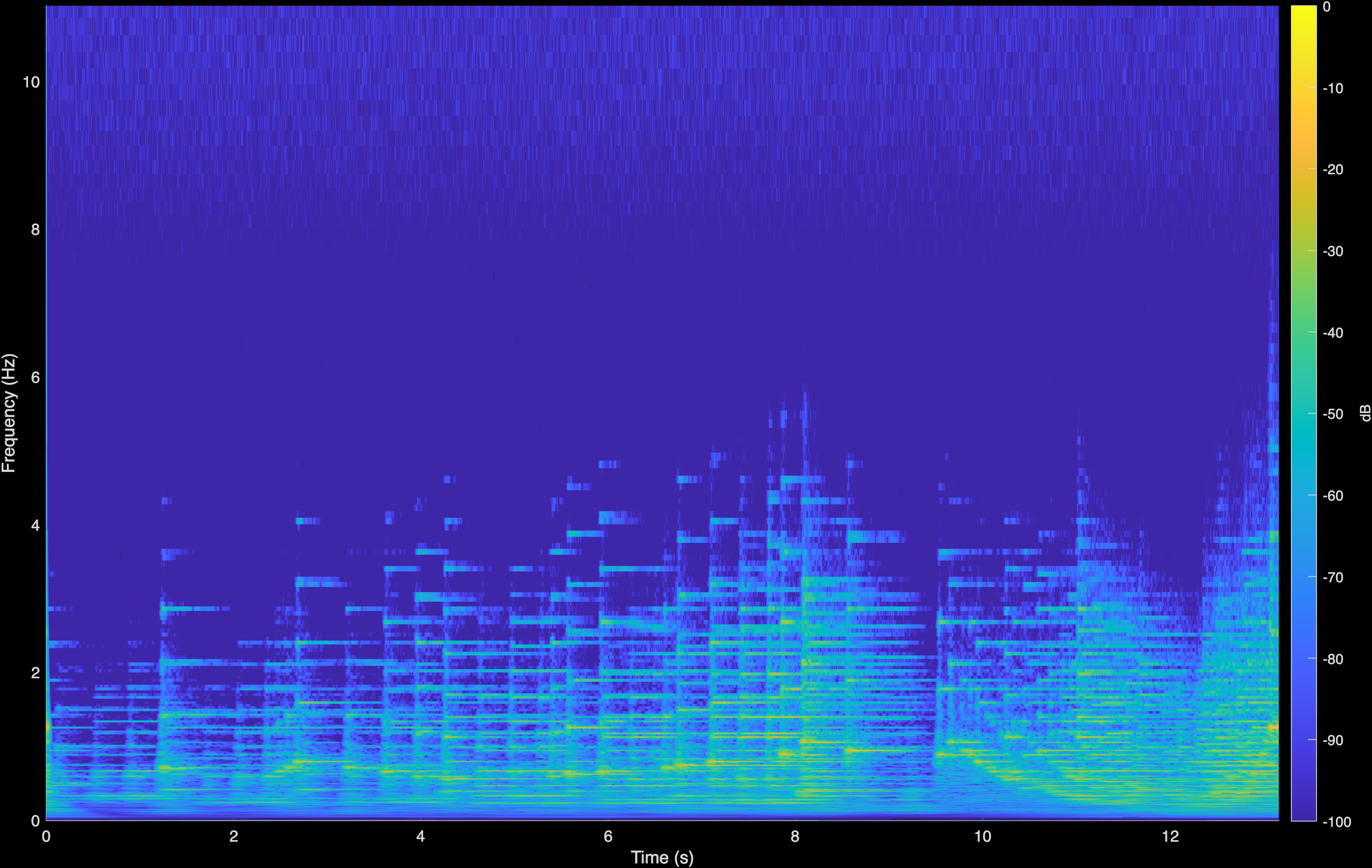

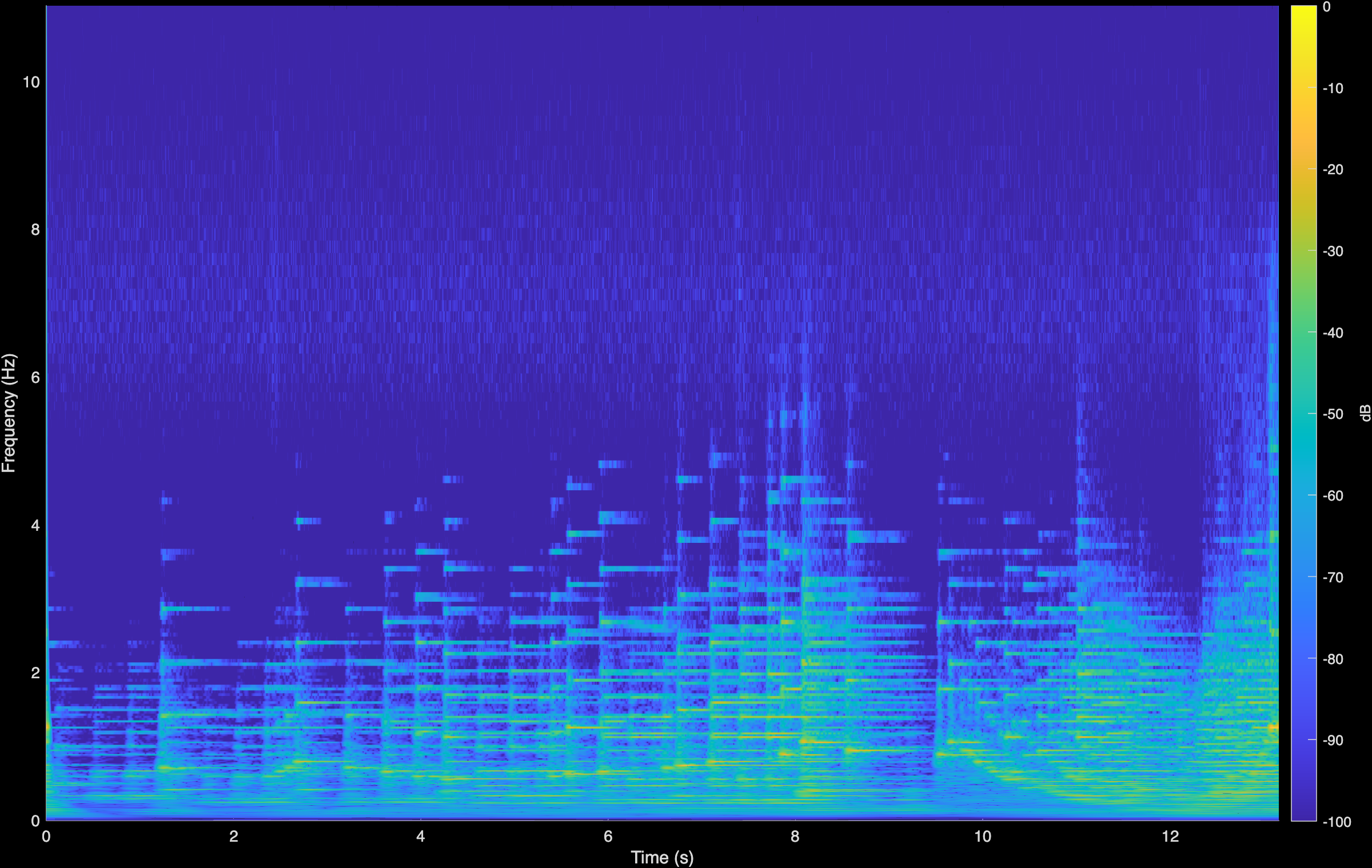

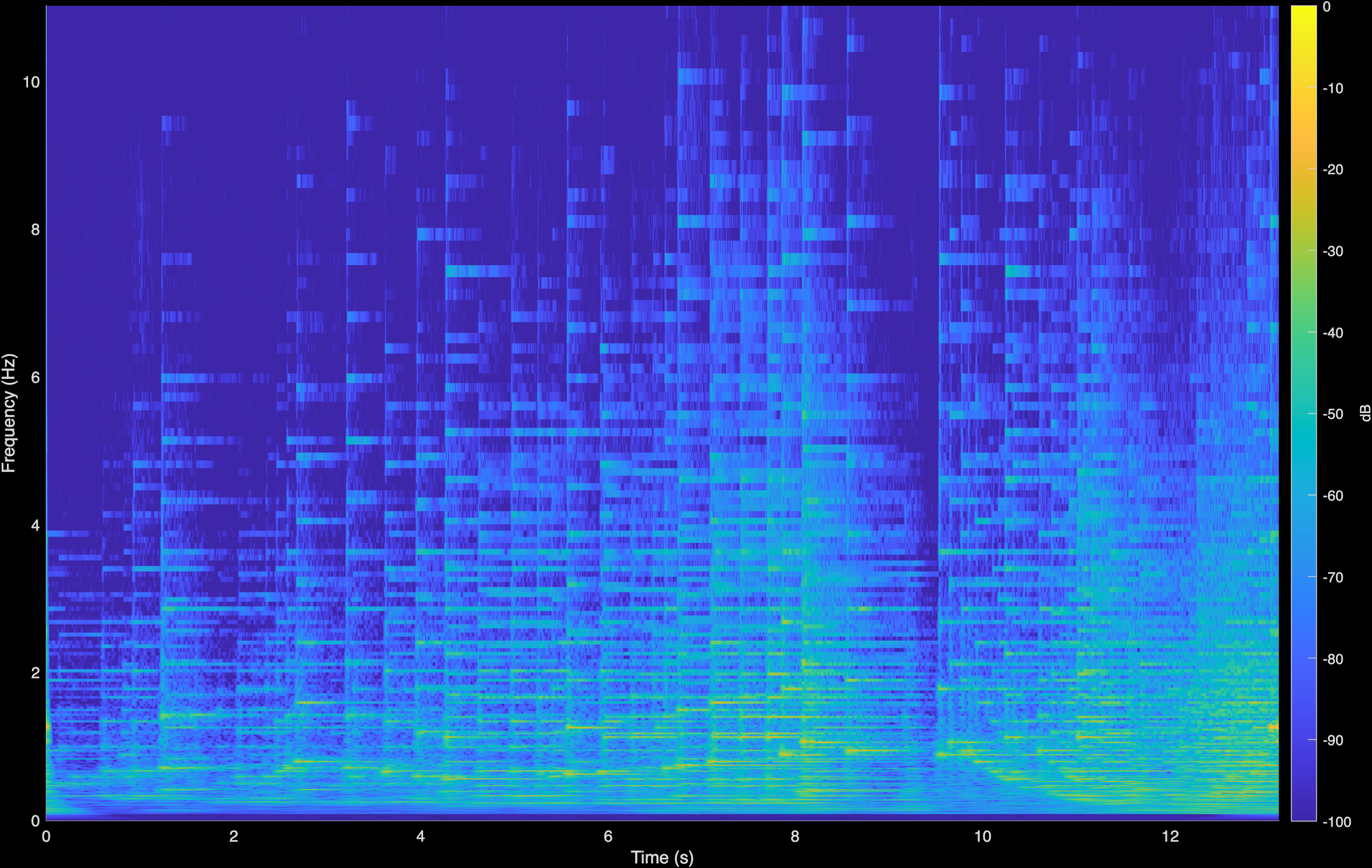

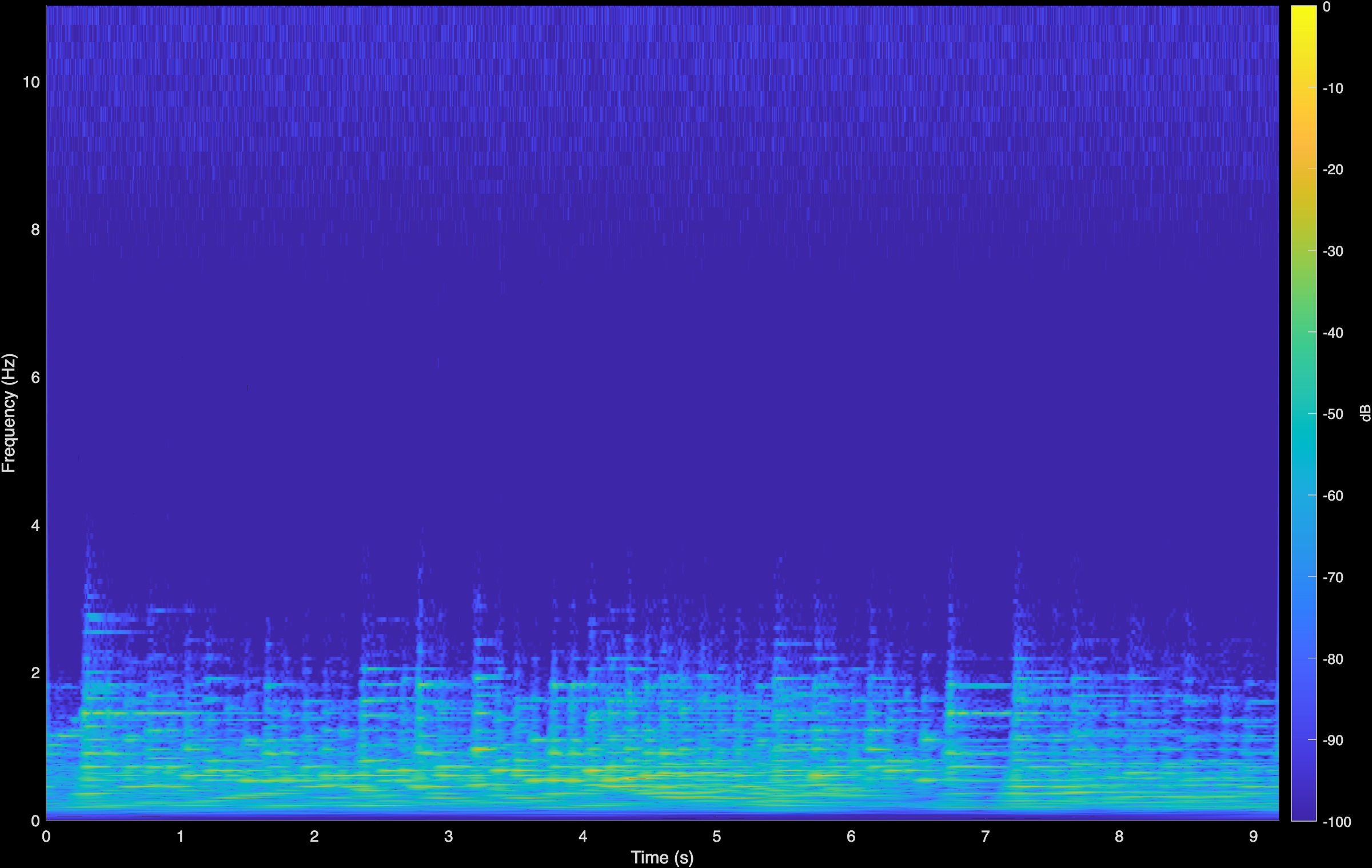

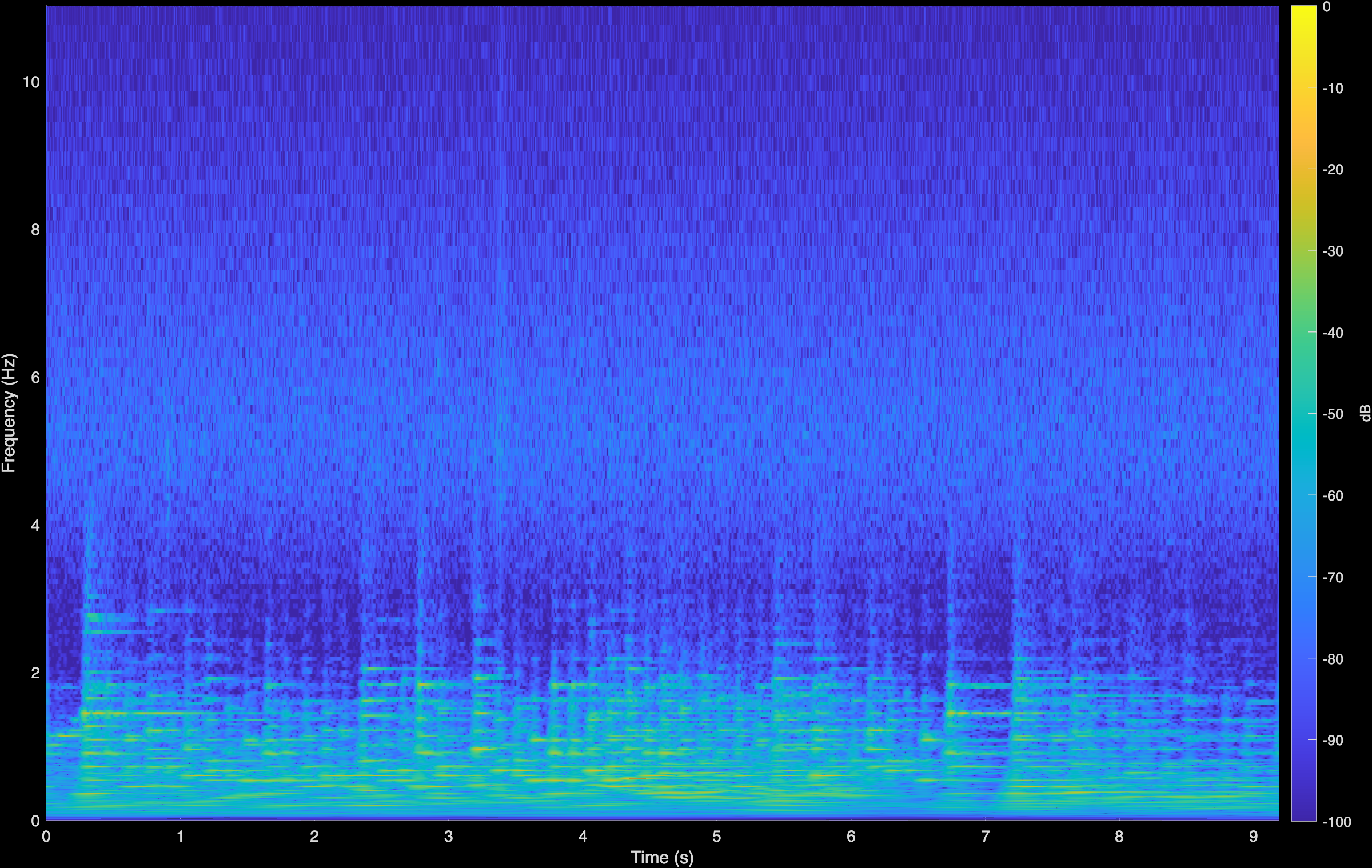

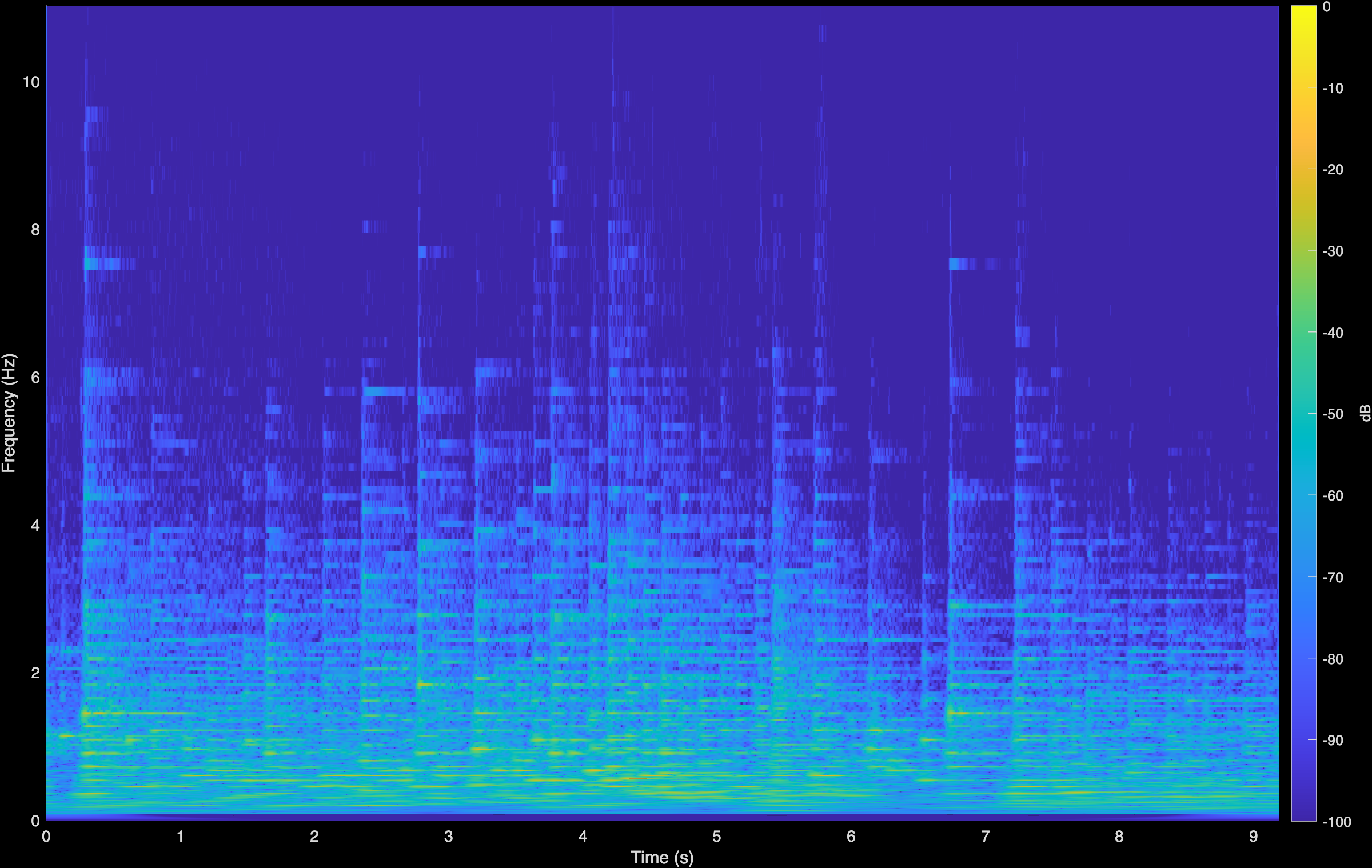

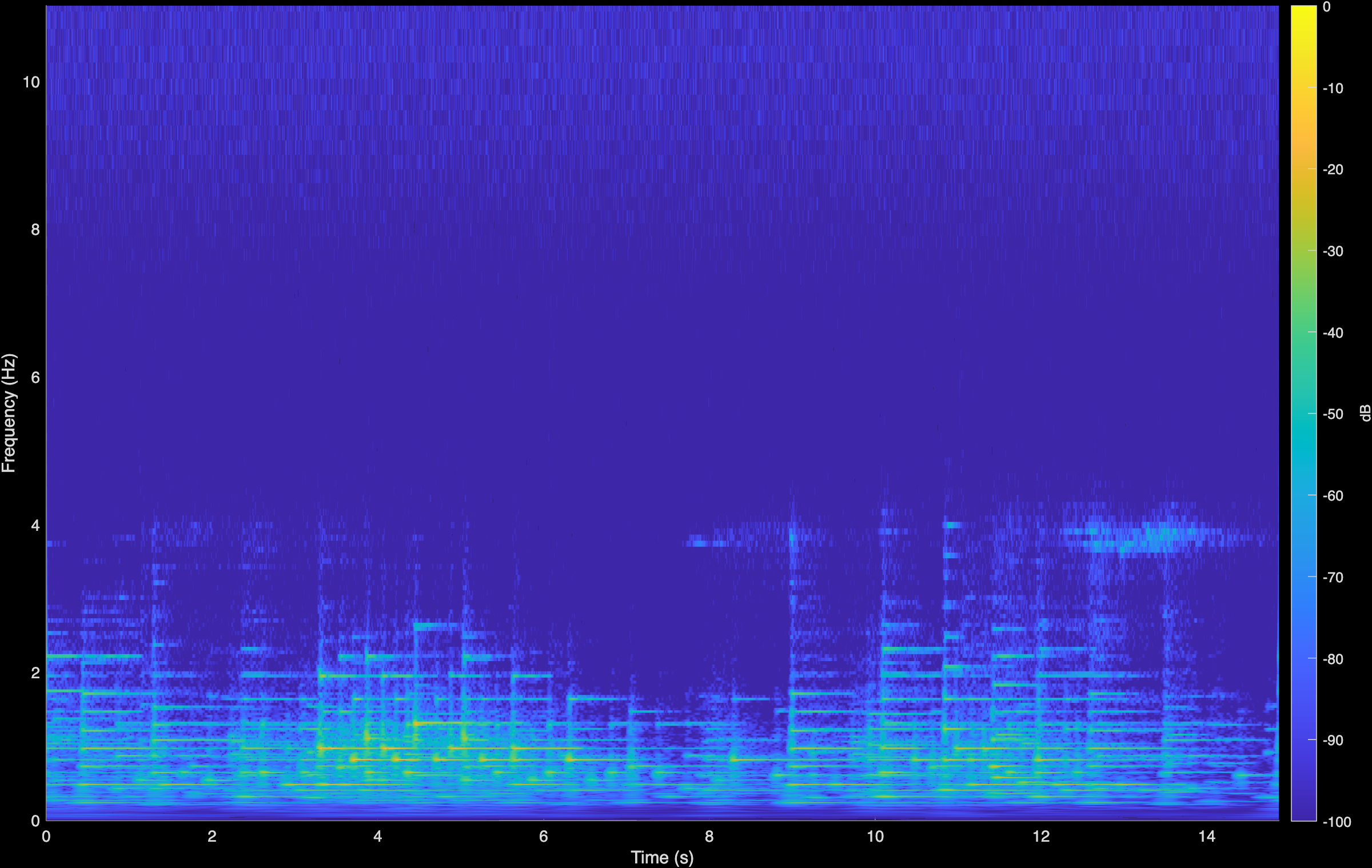

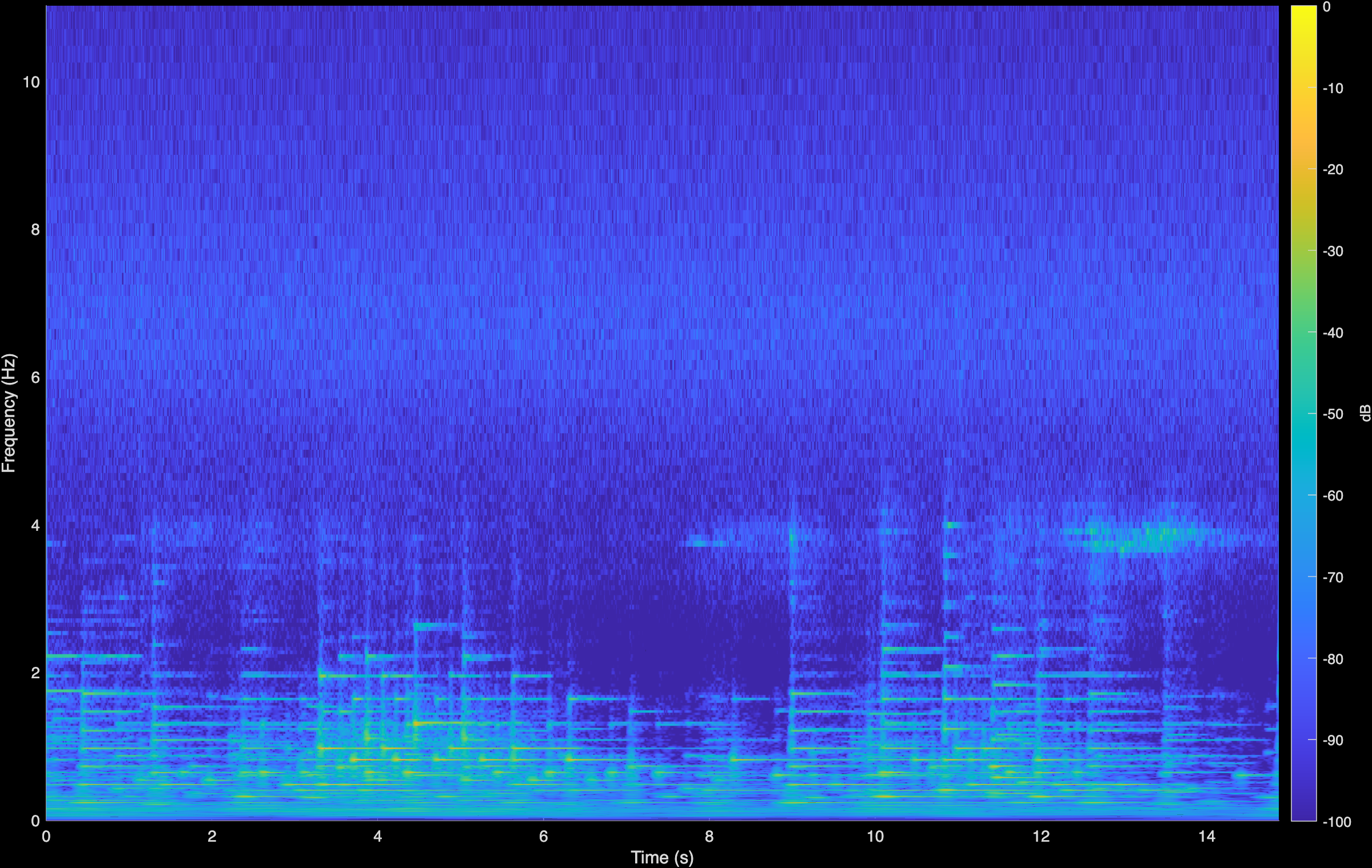

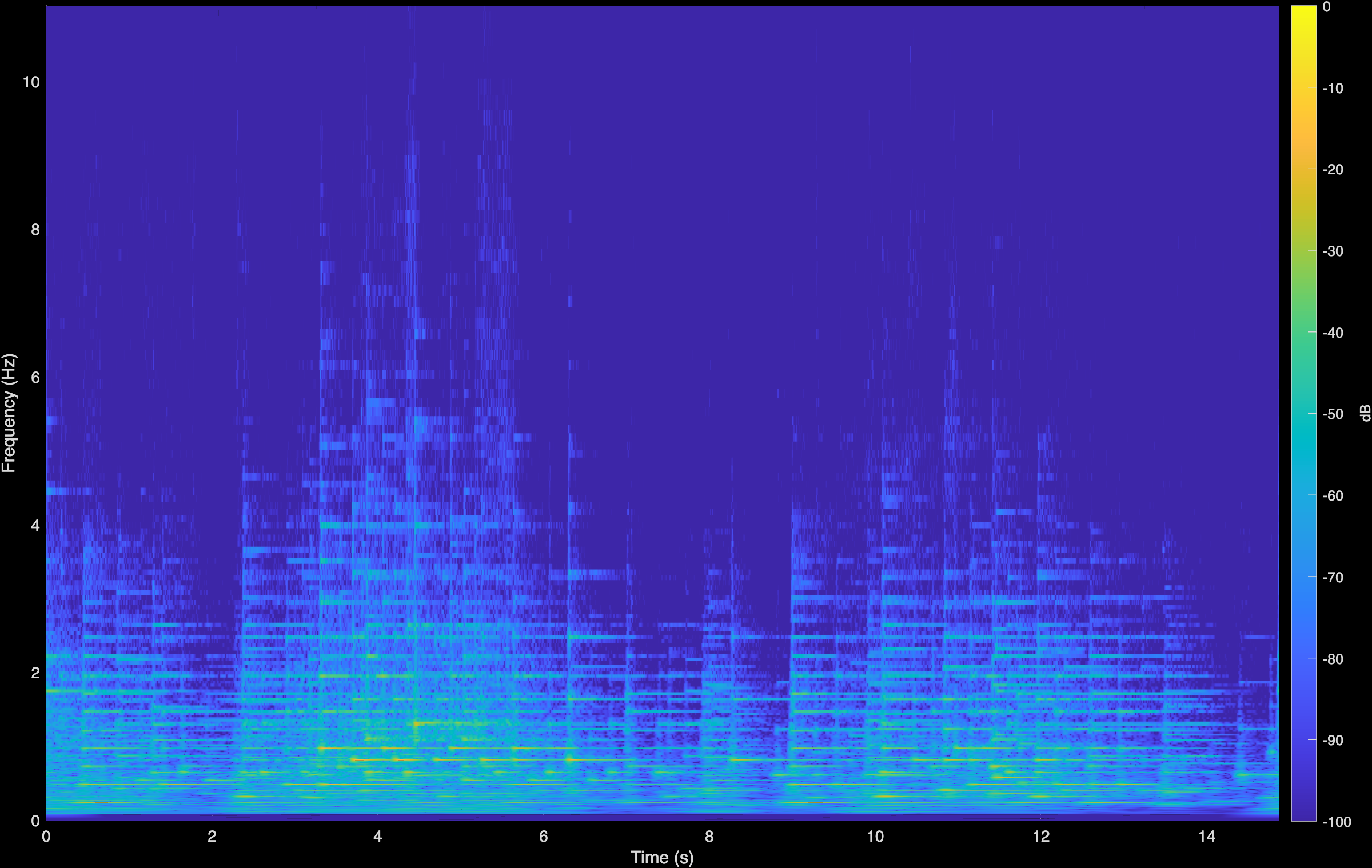

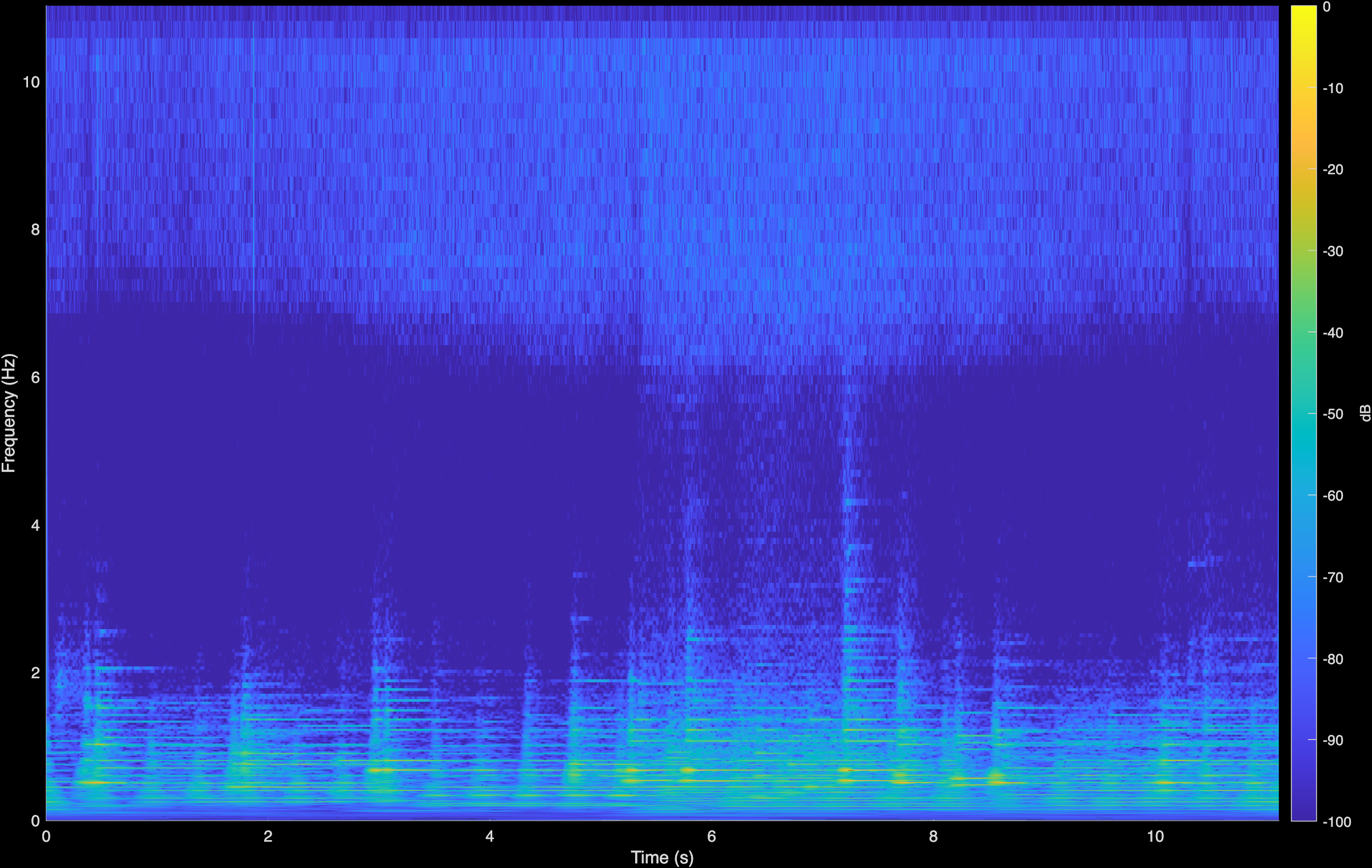

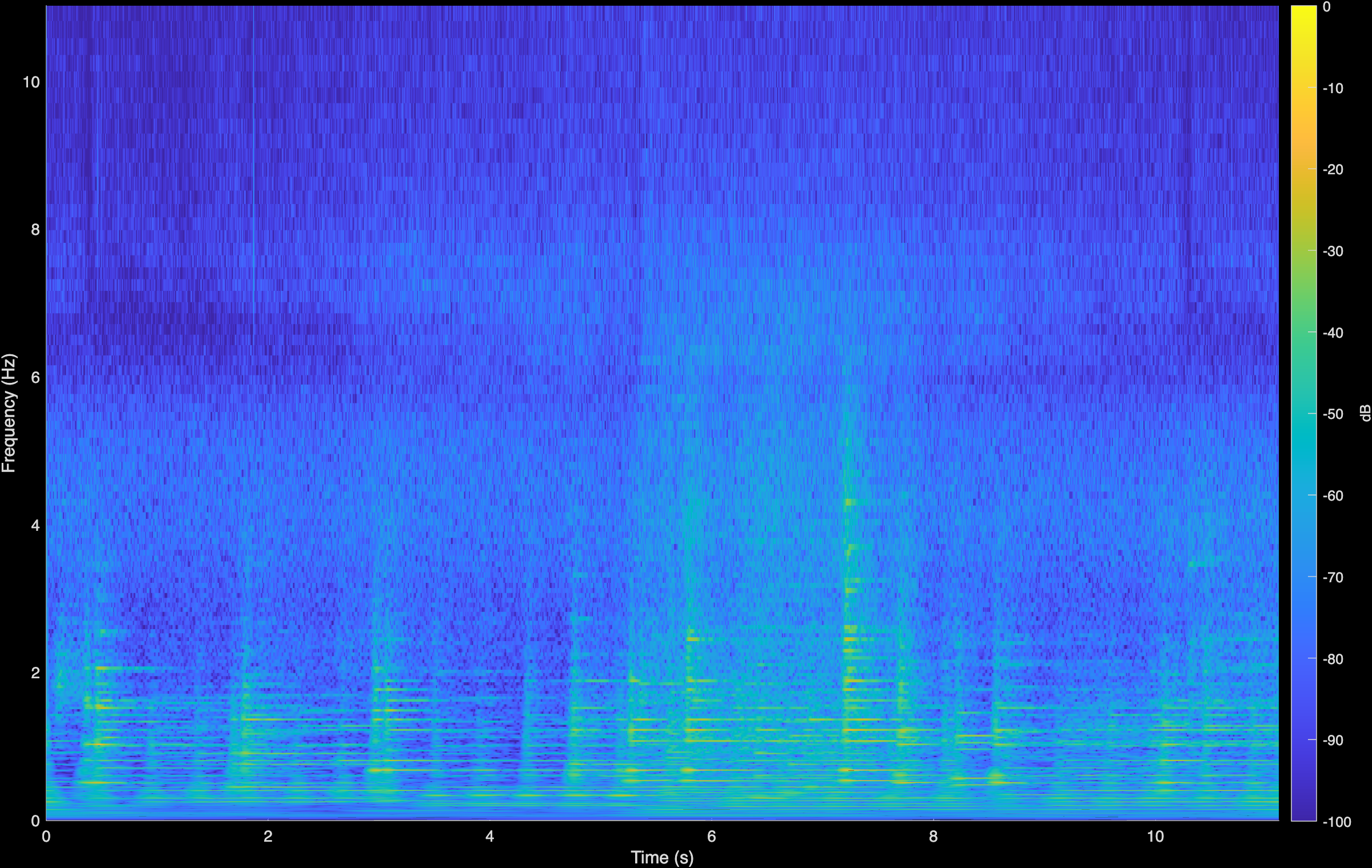

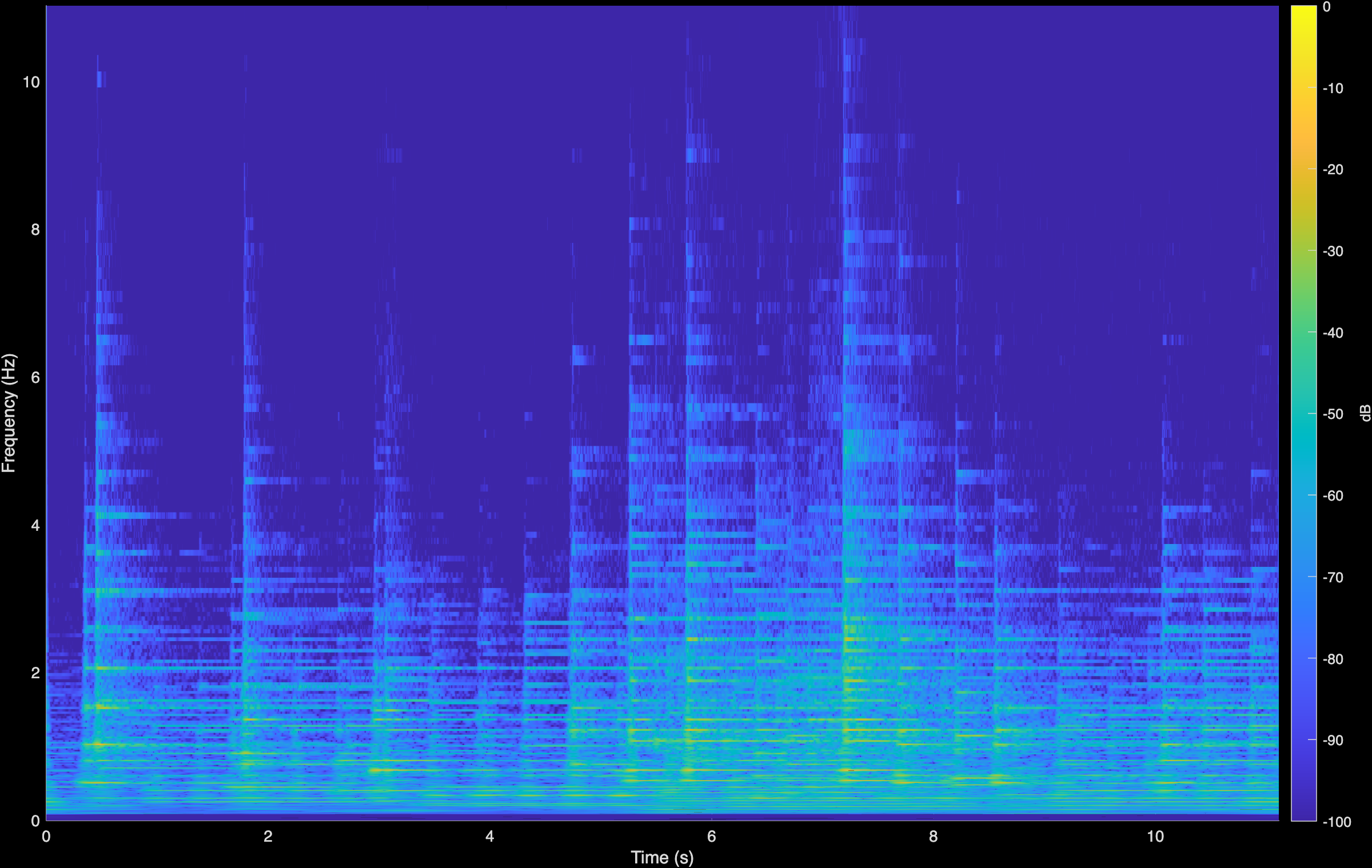

To demonstrate generalization beyond the spatial setting, we have conducted additional experiments on Blind Audio Restoration. We aim to enhance historical piano recordings corrupted by unknown degradations (i.e., the A(.) operator includes spectral coloration, additive noise and clicks, nonlinear effects, etc.). This is a fully blind setting since we neither assume an analytical form for A(.), nor do we estimate it during inference. Instead, we employ our proposed contrastive model—trained with pairs of clean and degraded audio data—to learn powerful representations. Our clean data are recordings from the MAESTRO dataset [1] while the degradations include low-pass filtering, clipping, additive Gaussian noise, etc. Using a pretrained diffusion prior [2], we observe improved audio quality of these recordings; CQT plots demonstrate that the model achieves bandwidth extension, improved dynamics and a reduction in noise in the high frequency. We compare against LTAS [2], an equalization technique that seeks to align the Long-term Averaged Spectrum of the audio with a reference set.

The table below shows the quantitative metrics of Fréchet Audio Distance (FAD) [3] using VGGnet and PANNs [4] for the degraded recordings, LTAS baseline, and CoGuide.

| Method | VGG ↓ | PANN ↓ |

|---|---|---|

| Degraded (Original) | 2.52 | 0.39 |

| LTAS | 2.88 | 0.27 |

| CoGuide (Ours) | 0.84 | 0.19 |

We also show qualitative audio samples with spectrograms below for comparison across different composers and pieces.

Beethoven

Original (Degraded)

LTAS

CoGuide

Chopin - Fantaisie

Original (Degraded)

LTAS

CoGuide

Chopin - Mazurka

Original (Degraded)

LTAS

CoGuide

Chopin - Sonata

Original (Degraded)

LTAS

CoGuide

Chopin - Waltz

Original (Degraded)

LTAS

CoGuide

Horowitz

Original (Degraded)

LTAS

CoGuide

Horowitz - Etude

Original (Degraded)

LTAS

CoGuide

Liszt

Original (Degraded)

LTAS

CoGuide

Mozart

Original (Degraded)

LTAS

CoGuide

Moszkowski

Original (Degraded)

LTAS

CoGuide

Rachmaninoff

Original (Degraded)

LTAS

CoGuide

Jungmann

Original (Degraded)

LTAS

CoGuide

References

[1] Hawthorne, Curtis, et al. Enabling factorized piano music modeling and generation with the MAESTRO dataset. arXiv preprint arXiv:1810.12247 (2018).

[2] Moliner, Eloi, et al. A diffusion-based generative equalizer for music restoration. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.18636 (2024).

[3] Kilgour, Kevin, et al. Fréchet audio distance: A reference-free metric for evaluating music enhancement algorithms. arXiv preprint arXiv:1812.08466 (2018).

[4] Kong, Qiuqiang, et al. PANNs: Large-scale pretrained audio neural networks for audio pattern recognition. IEEE/ACM Transactions on Audio, Speech, and Language Processing 28 (2020): 2880-2894.